Team Fur News

Team Fur News

Of Trout and Peonies

By FUR-FISH-GAME Editor, John D. Taylor

Fly fishing is a great way to spend a spring day. Photo: Henry Fraczek/Unsplash

Perched above an undercut bank on the East Branch of Codorus Creek, in York County Pennsylvania, I held a Zebco 202 spincasting combo in my 8-year-old hands. My line fell into a deep green pool, where muskrat bank dens – something I would appreciate in a few years – marked the edge of land and water. Meanwhile, bright spring sunshine warmed new grass sprouting among the stems that drooped over the creekbank. That warmth created a heavenly pure spring odor – a blend of fishy water, mayapples, grass, tree buds, mud, kid, and a worm can.

We were trout fishing, my father and I. He was opposite me, wading in the water, his open-faced spinning rig held ready for a bite, line in his left hand.

Since it was the trout opener, the creek well stocked with trout, we were not alone. Kids my age also with Zebco rigs, rowdy teenagers carrying minnow buckets, and men in hip boots and fishing vests with worm holders on their belts stomped up and down the creekbank, seeking a place to fish. Some had camped along the creek overnight to claim their “hole.” Dad and I had arrived early that morning to park in a long line of vehicles crowding the rural road.

Sitting, legs dangling over the bank, I glanced at my rod tip. Dad’s idea of fishing was to put bait on the bottom and wait for a bite. So, my rig, like his, was a No. 6 Eagle Claw hook tied to 8-inches of monofilament leader wearing red beads and a spinner blade. Several large split shots kept it on the bottom. Bait was nightcrawlers we’d collected by flashlight after a rain.

With all the movement along the creek, waiting for a bite seemed kind of boring to a kid – I’d already snarled my reel several times trying to cast, and Dad patiently unsnarled it – but I persisted. However, when my line moved against the current, and the rod tip bounced, something tugging on it, I heaved up a cold, slippery, 10-inch rainbow trout.

I’d caught my first trout and was darned excited about it.

* * *

As I grew older, Dad and I expanded our trout fishing territory, visiting other York County creeks. Otter Creek, a spritely little freestone stream that flowed from southern York County’s farmed uplands towards the Susquehanna River, was such a place. You could hop across the headwaters, but further downstream, the creek widened, and water in some holes was deeper than a 6-foot man’s chest waders. Mostly, it was about 15 yards wide and about 3 feet deep.

My maternal grandmother, Grandma Keller, enjoyed trout fishing almost as much as her grandson. She fished southern York County waters, where she grew up, particularly Muddy Creek. When she saw I lacked some proper trout gear, she offered a pair of hip boots that no longer fit her. Even though they were too big for my 10-year-old feet, Grandma’s hip boots were an opportunity to wade like other anglers, one I couldn’t pass up.

Otter Creek ran high, cold and fast that opener. But I started out across some shallow riffles, water I thought I could handle, Zebco in hand.

Facing upstream, the first few yards were easy. Halfway across the creek, water rushing against my hip boots, I snagged a foot on a rock and tripped, splashing headfirst into the creek. Those boots quickly filled with water and drug me downstream, embarrassing because other anglers witnessed my floundering.

I hollered for Dad, and he came running up along the bank, fetched his errant son out of the drink and took me back to the white, wood-paneled station wagon to dry off and change clothes. My parents’ forward thinking including a change of clothing. While I dried out, we ate the lunch Mother had packed. She always wrote something poetic on the napkins, but from that opener forward, the notes usually mentioned not falling in.

* * *

I joined the 7th grade fly-tying club to be with my friends. I didn’t know much about fly fishing, let alone tying flies, but when we started spinning feathers and fur around hooks, I enjoyed it, got good enough that my uncle, Dave Reichard, was willing to swap a fly rod and reel for a collection of flies I tied for him.

The rod was fiberglass, the reel a heavy automatic. The rig wasn’t balanced, but it was mine. You pulled the line out of the spring-loaded reel, cast, then fetched it back by pressing your pinky on the handle close to the grip. Strong springs zipped that line back fast.

I practiced casting in the high school band’s practice field, across from my parents’ house on the hill above the Dallastown High and Middle School buildings. After school, I’d be out in the field, Lefty Kreh’s tiny how-to fly cast book in front of me, trying to make it look like I knew what I was doing. With no obstacles behind me, I made some long casts. Smart-aleck high school kids, stuck after school in detention or for sports, drove their old cars past shouting, “Catching anything?” I’d tuck the rod under my arm, hold my hands wide apart to show them the size of the “yard trout” I’d hooked.

At 15, I was ready to use that fly rod. Dad and I were fishing Muddy Creek regularly then. The creek was misnamed – except after a heavy thunderstorm, when topsoil washed off spring-plowed farm fields surrounding the drainage. It was big water, maybe 30 yards wide in most spots, with some deep holes.

I’d learned by then that my father’s fishing style wasn’t mine. I liked to hunt fish, not sit and wait for bites. That opener I longed to fish Muddy Creek’s fly-fishing-only section. Dad didn’t mind fishing the bait section below that area, so, we parted company; him going downstream, me always up.

Just above a slight creek bend, I entered the water, worked my way towards a rock-strewn green water “hole” on the far side of the creek, where a downed oak lay partially submerged, parallel to the creek.

I cast one of my black Wooly Buggers at the upstream end of the log, the fly and two BB split shots plopping perfectly into the water, to wash past the log, a likely trout lie. The red-tailed fly imitated none of Muddy Creeks’ aquatic life, but it caught panfish in Lake Redman so I considered it lucky. About halfway through the float, the line stopped. I set the hook and netted my first trout on a fly of my own creation. What a feeling.

* * *

By the mid-1980s, I’d become a pretty good fly angler, at least on local waters, particularly Muddy Creek. Because I also wrote a newspaper outdoor column, Charlie Meck, a renowned Pennsylvania fly fisherman, drafted me to show him Muddy Creek for a book he was writing, “Pennsylvania Trout Streams and Their Hatches.”

Meck also wrangled Brian Burger, the Pennsylvania Fish Commission’s local waterways conservation officer, to help with the project. Burger knew Codorus Creek’s fly fishing area. So Meck, Burger and I met in town, loaded into my Bronco II and drove down to Muddy Creek. I showed him the fly section, told him what I knew of its insect hatches. Then we headed west, to Codorus Creek.

We wound slowly along the road that paralleled Codorus Creek, Burger in the back seat of the truck. Suddenly, in his law enforcement voice, he commanded me to stop. I did. He told Meck, riding shotgun, to hop out, so he could get out.

Next thing we knew, Burger was trotting towards an angler who’d just put another illegal fish on his stringer. How Burger saw that from the dog-snootered rear window of that truck, I’ll never know. But my respect for him grew immensely.

Meck wrote his book and sent me a copy. It quickly became my fly-fishing bible. Meck listed a slew of fly-fishing streams, sharing the timing of their aquatic insects hatches – everything from early blue-winged olive mayflies, to the big bugs of May and June, even late summer’s tiny midges. More important, he included his recipes for tying each life stage of these flies, from nymph, caddisfly or damselfly larvae to the emerging insects, duns and spinners. This opened up a whole new world to me. My previous flies mimicked attractor patterns – Royal Coachmans or Henryville Specials – not specific insects. Meck showed me how to imitate natural stream life and offered a slew of new waters to explore.

For the next several years, Dad and I traveled to fish some of those waters. We picked bait fishing streams, so Dad could continue dunking worms.

For 1989’s trout opener, I decided I’d fish only flies for trout, particularly nymphs, unless a visible hatch was taking place. I’d use G. E. M. Skues’ upstream nymphing techniques, and a Joe Humphrey/Penn State-style tuck cast to deliver the fly.

We started that opener on Conococheage Creek, west of Chambersburg. Dad went downstream, I went up. Before noon, I returned with a limit of trout, all caught on Hendrickson or Quill Gordon nymphs. Dad’s eyes bugged out, and I felt like I’d mastered something – thank you, Charlie Meck. I tried, for a time, to get Dad into fly fishing. But it wasn’t his cup of tea. He preferred waiting for a bite.

* * *

At the end of May, the wonderful scent of blooming peonies arose from my paternal grandmother’s Red Lion, Pennsylvania, flower bed. At 89, Grandma Taylor was still mowing her own lawn. But it was getting a little much for her. When asked to take over her lawncare, I happily agreed. Yet I really wanted to go fishing, too. The Green Drake hatch on my favorite stream, Penns Creek, was taking place. Couldn’t the grass wait? Not for Grandma.

Walking past her blooming peonies, that wonderful aroma wafting into my nose, I came to associate peonies with the Green Drake hatch, and Grandma.

The first time I saw the hatch was on an evening near Memorial Day in the late 1990s. Penns Creek is a big limestone stream – more like a river – a rich environment for trout and aquatic insects. It’s maybe 75 yards across, with deeper holes of 15 feet or more.

Standing midstream that night on the fly-only stretch, I was tying a Meck-style Green Drake nymph – the big Coffin Fly spinners had yet to descend – to my leader, when I looked up to witness thousands – no, millions – of 2- to 3-inch mayflies literally dancing in the canopy above the stream.

They fluttered up, sunk back down; fluttered up, sunk down. A mating dance? In this, I saw the symmetry of it as the hand of the Creator at work, magnificent nature on full display. The spectacle made it hard to concentrate on fishing, I was too filled with awe. And that was okay – until a little later, when the big white Coffin Fly spinners landed on the water and summoned spectacular rises from hidden fish all over the stream. The beauty of that experience has stayed with me far more than the number of fish I caught.

I’ve fly fished in some famous U.S. trout waters – the Madison River, for example, fly fishing’s Mecca. But I found Mecca too crowded, the current usually way too fast for pleasant fishing. The nearby Ruby River suited me. I even had a ruffed grouse flush and land on my head on the Ruby. That bird, a male, would simply not leave me alone. Still, my trout-fishing heart remains with Penns Creek, the Green Drake hatch, and Grandma Taylor’s peonies in bloom.

Be Bear Aware This Spring

Removing attractants like bird feeders in the spring can reduce bear problems. Photo: bearwise.org

Wildlife agencies across the nation are urging anglers, spring turkey hunters, hikers, campers, backpackers, anyone who ventures outdoors to be especially bear aware this spring.

In Wisconsin, for example, black bears have emerged from their winter dens in search of food and potential new territory. These explorations sometimes cause unexpected interactions between bears and people. Although black bears are much more common in the northern half of the state, southern Wisconsin has seen more black bear activity in recent years. To avoid potential conflicts, Wisconsin’s Department of Natural Resources (WDNR), along with most other state wildlife agencies, says it’s important to recognize bear attractants and take steps to reduce or remove these attractants whenever possible. This includes:

• Removing bird feeders – Bird feeders provide a high-density food source with bears returning to a feeder often. Accumulations of seeds below the feeders should also be cleaned up.

• Trash and recycling container odors – Bears have keen noses and are attracted to food waste. Rinsing food cans and bottles before throwing them away and storing meat scraps in the fridge or freezer until garbage day, can reduce garbage and recycling container odors. Storing trash and recycling containers in a closed building also helps. Commercial dumpsters should be locked.

• Scented products – When outdoors, avoid wearing scented products. These can attract bears believing their foodstuffs.

• Pets and pet food outdoors – Bears can be skittish, but they are highly food-motivated. They may also defend themselves or attack pets when provoked. Limiting how long pets are left alone outside and leashing them when recreating, helps. Also, remove pet food and bowls. Those with chicken coops or apiaries should consider installing an electric fence to protect flocks and hives.

• Grills and picnic tables– Barbeque grills and picnic tables often have leftover food scraps that can attract bears. Same with meat smokers. Clean surfaces after use.

• Don’t feed bears – Never feed a bear, intentionally or not. When bears associate people with food, there’s trouble for both.

• Bear encounters – How to handle bear encounters changes with the type of bear involved. WDNR says if you encounter a black bear, try to scare the bear away by making loud noises (clanging pots and pans) or throwing objects in the bear’s direction from a safe location. Make sure the bear has an escape route, never corner a bear, and don’t turn your back on the bear or run away. If you’re in the woods or along a stream, stay calm and don’t run. Wave your arms and make loud noises to scare the bear. Back away slowly and seek a safe location from where you can wait for the bear to leave. Never approach a bear. For your safety, don’t attempt to break up a fight between a pet and a bear. Neighbors should alert neighbors to any bear activity to take precautions.

• In the West, Montana’s Fish, Wildlife and Parks Department (MFWP), along with wildlife agencies in Wyoming, Idaho and Alaska, deal with both grizzlies and black bears. Grizzlies in the lower 48 states are listed as threatened under the Endangered Species Act. MFWP urges anyone outside working or recreating, to be aware that bears are out there, too, typically from March through the end of November. And grizzlies can now be found anywhere west of Billings. Being bear aware means you assume bears can be around, even if you don’t see them. MFWP suggests removing attractants. In addition, especially in grizzly country, travel in groups; avoid carcass sites and concentrations of ravens and other scavengers; and watch for grizzly sign like scat, torn up logs, turned over rocks and partly consumed carcasses. Also, make noise, especially near streams or in thick forest. This can be the key to avoiding encounters. Most bears will avoid humans. MFWP also urges anyone recreating or working outdoors to carry bear spray and know how to use it – especially if the bear is 25 feet away. The recommendation is if you feel threatened, to stand your ground and use bear spray.

• Most states have website pages and phone numbers devoted to how to handle recurring issues with nuisance bears. Visit your state’s wildlife conservation agency to locate these contact numbers and consider that people and bears can live in the same area with little conflict by following some basic rules. For more information on living responsibly with bears, Bearwise.org.

New Old Book For Sale

The FUR-FISH-GAME Bookmarket recently added a classic book for sale, Where the Red Fern Grows, by Wilson Rawls. Considered by many to be one of the most important young adult books ever written. You probably read it, yourself. But if your kid or grandkid hasn't, it's time to change that. Or maybe you want to add it to your bookshelf so you can reread it yourself. To commemorate more than fifty years in print, this special edition includes a new hardcover, a note from Newbery Medal-winning author Clare Vanderpool, as well as historical materials to enrich this treasured novel. Timeless classic about a boy who saves two dogs – and who save him in return. Recommended ages 8 and up. Order from https://www.furfishgame.com/store/new_products.html

Parasite Discovered in Wild Wisconsin Trout

Trout swim in a creek. Photo: rigel/Unsplash

The Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources (WDNR) is urging anglers to properly clean their gear after discovering the parasite Myxobolus cerebralis in Elton Creek in Langlade County. Myxobolus cerebralis is a microscopic parasite that damages the cartilage and nerve tissue of trout and salmon and has been known to cause whirling disease. Elton Creek is a Class 1 trout stream that recently tested positive for Myxobolus cerebralis below Elton Springpond and at Highway 64. “It’s unknown how Myxobolus cerebralis will impact our local trout populations at this time,” said Justine Hasz, DNR Fisheries Management Bureau Director. “In some states where the parasite has been found, trout and salmon have developed whirling disease, which has negatively impacted their local populations. However, other states with the parasite have seen no evidence of fish with whirling disease nor have they seen their trout and salmon populations impacted.” Although no fish have been discovered in Wisconsin with clinical symptoms of whirling disease, WDNR is implementing a surveillance program to determine if any additional trout populations have been affected. Anglers should watch for trout or salmon displaying any signs of whirling disease – blackened tails, skeletal deformities or swimming in circles – and report sightings to their local fisheries biologist. The parasite is only capable of infecting trout and salmon, with rainbow and brook trout thought to be most susceptible. It cannot infect other fish species and poses no threat to humans or household pets like cats and dogs. Though cooking harvested fish according to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s food safety guidelines is always recommended, anglers are encouraged to never consume fish that appear sick or diseased. This parasite is nearly impossible to eradicate once it has been established, but steps can be taken to limit the spread. WDNR wants anglers to clean and disinfect their gear after fishing and wear rubber-bottomed boots or waders. All water, aquatic vegetation, and/or mud that might contain the parasite should be removed from their fishing equipment streamside before being thoroughly cleaned. All fishing equipment, including boats, trailers, boots, waders, nets and float tubes should then be dried completely before being used again. It’s also important to remember to not dispose of fish tissue or by-products into bodies of water to prevent the spread of this and other fish diseases.

Michigan E-Bike Regs May Change

Cyclists enjoy the trail at Van Buren State Park near South Haven

in Van Buren County. Photo: Tyler Leipprandt/MDNR

Operation of Class 1 electric bicycles on state park-managed nonmotorized trails open to bicycles could expand under a proposed Michigan Department of Natural Resources (MDNR) land use change as early as this spring. Under current Michigan law, only Class 1 e-bikes – e-bikes that are pedal-assisted and can go up to 20 miles per hour – are allowed on improved surface trails, which are trails that are paved or consist of gravel or asphalt. Current law also allows for local entities to expand or further regulate e-bike usage in their respective communities. The proposed DNR land use change would expand allowable e-bike use to include Class 1 e-bikes on natural surface, nonmotorized trails on state park-managed lands open to bicycles. Also, the proposed change would allow operation of Class 2 e-bikes, which are throttle- and pedal-assisted and can travel up to 20 miles per hour, on both linear paved trails and state park-managed natural surface trails so long as a cyclist has applied for and received a permit to do so. Currently, Class 2 e-bikes are allowed with a permit only on nonmotorized, natural surface trails (such as mountain bike trails). This expansion would not apply on wildlife or state forest land trails that are open to bicycles. Also, Class 3 e-bikes, which are pedal-assisted and have a maximum speed of 28 miles per hour, would remain prohibited on any state-managed land under the new policy. Some 3,000 miles of nonmotorized state park-managed trails open to bicycles could be affected by the proposed change, if approved. Signage indicating allowable e-bike use would be placed at trailheads. Learn more at Michigan.gov/DNR/Ebikes.

Iowa's Bumble Bee Project Seeks Volunteers

A bumble bee gather pollen from a wildflower. Photo: IDNR

A new Iowa project is looking for volunteers to help researchers track and monitor the state’s at-risk bumble bees. The Iowa Bumble Bee Atlas is a collaboration between the Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation, Iowa State University and the Iowa Department of Natural Resources (IDNR) that aims to understand native bumble bee distributions and their habitat needs. Iowa is home to at least 14 bumble bee species that play essential roles in sustaining the health of the environment, from pollinating native wildflowers to flowering crops in farm fields and backyard gardens. Unfortunately, several bumble bee species native to Iowa experienced alarming declines and face an uncertain future. “The recent listing of the rusty patched bumble bee as an endangered species by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service is increasing the need to collect data on the occurrence of all bumble bee species in our state,” said Dr. Matthew O’Neal, professor of entomology at Iowa State University. The effort is one of a growing number of Bumble Bee Atlas projects run by the Xerces Society and their partners in 20 states. In 2023 alone, more than 900 individuals participated in the Atlas, documenting over 20,000 bumble bees. The volunteers have discovered species previously thought to be gone from their states, contributed to new field guides and rapidly improved scientists’ understanding of bumble bee populations across the United States. The information gathered provides a modern snapshot of bumble bees and serves as a benchmark to compare with future conditions. The data can assess bumble bee ranges, phenology and habitat associations. It can also understand how these patterns have changed over time. This information can then be used to design conservation guidelines for at-risk species and create habitat management guidance for land stewards. The Iowa Bumble Bee Atlas is open to anyone with interest in pollinator conservation. Training will be provided on how to complete surveys, take high quality photographs of bumble bees, and submit observations using a platform called Bumble Bee Watch. Interested volunteers can sign up for the first online training event and view other events at bumblebeeatlas.org.

A.R. Harding Publishing Summer Hours

FUR-FISH-GAME offices will be testing out early summer hours, when call volume is at its lowest. The office will be open Monday through Thursday, 9:00am to 4:30pm EST in the months of May and June. Beginning in July we will resume our regular hours of Monday through Friday, 9:00am to 4:30pm EST.

Youth Turkey Hunters Tagging Many Gobblers

Youth turkey hunters in two states tagged many gobblers during their special season. Photo: ODNR

Youth turkey hunters in two states have tagged many gobblers during their special season. Illinois youth hunters, for example, harvested a preliminary total of 2,006 birds during the 2024 youth turkey season, breaking the previous harvest record of 1,733 set in 2020. The youth season was held March 30 - 31 and April 6 - 7. More than 6,000 youth turkey permits were issued, compared to 5,283 in 2023. In 2023, a total of 1,297 youth turkeys were taken. The top five counties for harvest during this year’s youth season were Randolph, 71; Fayette, 66; Jefferson, 63; Marion, 62; and Pike, 54. A preliminary total of 160 wild turkeys, or 8% of this year’s harvest, were taken on public land. Youth turkey hunters in Ohio also checked 1,785 birds during their special youth-only hunting weekend, April 13 - 14, according to the Ohio Department of Natural Resources (ODNR) Division of Wildlife. The three-year average for wild turkeys taken during the two-day youth season (2021-2023) is 1,466 birds. In 2023, youth hunters harvested 1,823 turkeys on the corresponding weekend. The season was open to hunters 17-years-old and younger, and participants were required to be accompanied by a nonhunting adult. As of April 14, the ODNR Division of Wildlife has issued 6,539 youth turkey permits, which can be used throughout the 2024 wild turkey hunting season. The season limit is one bird, and only bearded turkeys may be harvested. The top 10 youth counties for wild turkey harvest were: Tuscarawas (62), Noble (60), Washington (59), Monroe (58), Jefferson (55), Belmont (53), Gallia (52), Muskingum (52), Coshocton (47) and Meigs (45).

Spring Highways and Turtles

A snapping turtle crosses a road. Photo: Texas A&M Agrilife

Forget the chicken — have you ever wondered why the turtle crossed the road? Throughout spring and early summer, drivers across the country are likely encounter turtles attempting to cross roads. These four-legged reptiles aren’t simply enjoying spring — they’re fulfilling a biological imperative. Common freshwater turtles typically begin mating between March and July. Later in the spring and early summer, they’ll start moving and searching for good nesting spots. Texas, for example, is home to 26 semi-aquatic freshwater turtles that begin emerging from waterbodies to lay eggs on land in May. While nesting specifications vary by species, females typically search for an area of soil with sufficient moisture, but far enough away from a body of water to prevent the nest from flooding. Many times, a road built across a waterway is the highest point nearby, so females will build their nests right next to the road. As a result, turtle roadkill is often high. A 2016 study, published in “Herpetological Conservation and Biology,” documented 850 road-killed turtles over a four-year period along a single stretch of road spanning an East Texas lake. Even turtles that don’t build their nest adjacent to a roadway may still be required to cross roads in search of an ideal nesting area. What can drivers do to help? Human safety takes precedence when driving. However, if possible slow down and navigate around the turtle. If you want to move the turtle to safety, pull over, park safely and, if no traffic is coming, grasp the turtle by its shell on either side and transport it across the road in the direction it was heading. Alternatively, a stick or other tool can be used to encourage the turtle to continue walking across the road. The most commonly seen turtles are likely red-eared sliders or box turtles, although snapping turtles may also be encountered. Snapping turtles can bite in defense, so avoid the front half of the turtle, use the underside of the rear of the shell and perhaps a back leg to move a snapper. Once a female turtle locates a nesting area deemed sufficient, she uses her back legs claws to excavate a hole in the soil and lay a clutch of eggs. She then covers the eggs with soil and returns to her original location.

Alabama’s Uphill Battle for Bobwhite Quail

The northern bobwhite quail is struggling to adapt to habitat changes across the South. Photo: ADCNR

When fence rows from small farms and family gardens crisscrossed Alabama – all the South – bobwhite quail flourished. However, with the arrival of large-scale farming and increasing urbanization, quail habitat along with wild bobwhites have significantly diminished, according to the Alabama Department of Conservation and Natural Resources (ADCNR). “Unfortunately, we can’t turn back the clock to the habitat we had at landscape levels in 1970 and prior,” said ADCNR’s Steven Mitchell. “We do have some private lands that manage for wild bobwhites, and they have to intensively manage year-round for wild quail. They have the resources to do that, and they have good populations there. When I say good populations, I’m talking about how many (dog) points per hour. Some places find four or five coveys per hour. That’s the old Southern style hunting off horseback and mule-drawn wagons. So, they’re moving, and they have some big running dogs. That’s how they can find those numbers per hour hunting. They have also put in the work on the habitat to have that number of wild birds.” ADCNR Upland Game Bird Coordinator Brandon Earls tries to improve habitat for quail whenever possible on the agency’s wildlife management areas. But this is difficult because state lands must be managed for multiple species. Still, there are areas that ADCNR considers “quail emphasis” areas, where management is more focused on improving quail habitat. Though bobwhite densities remain low, Earls noted, there have been some positive responses. One such place is the Boggy Hollow WMA within the Conecuh National Forest, cooperatively managed by ACDNR and the U.S. Forest Service. This acreage is being converted into bobwhite habitat through selective timber thinning and more frequent, smaller prescribed burns. Timber thinning increases sunlight reaching the ground, encouraging the growth of native grasses and forbs to provide food and nesting habitat for the quail. For the 2022-2023 season, Alabama had 9,427 quail hunters. Of those, 2,700 hunted wild quail and harvested about 27,000 quail. Including the quail plantations with pen-raised quail, hunters harvested more than 370,000 birds overall. Hunters can find numerous quail plantations across the state, but the greatest concentration in the Black Belt region. Visit www.alabamaquailtrail.com for a list of plantations and lodges that offer hunts on flight-conditioned, pen-raised quail. For more information about Alabama’s wild quail, go to www.outdooralabama.com/what-hunt/quail-hunting-alabama. “Ecology and Management of the Bobwhite Quail in Alabama,” authored by former ACDNR Wildlife Biologist Stan Stewart is there. For those who want to help monitor Alabama’s quail populations in by reporting quail calls, Quail Forever and its partners developed the “Bobscapes” mobile app (bobscapes.org) that allows users to report hearing a quail, which is then entered into a national database.

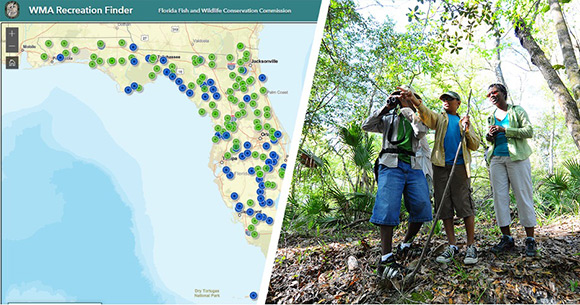

Florida Unveils WMA Finder

The Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission has a WMA Recreation Finder, an interactive virtual map for anyone looking to find outdoor experiences on public land. Photo: FWC

With more than 6 million acres of state-managed conservation lands, options for experiencing wild Florida can be difficult to narrow down. The Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission (FWC) recently unveiled its new WMA Recreation Finder, an interactive virtual map for anyone looking to find their outdoor experience on public lands. Users can create their ideal adventure by choosing from a variety of recreation experiences, trail types, amenities and accessible facilities. The map also includes detailed information to plan a visit, including hours of operation, entrance fees, directions, links to the WMA website and regulations. FWC’s video tutorial for the Recreation Finder helps new users navigate the site. It’s available at youtu.be/ORZ9NgRZf-c. Florida has one of the nation’s largest state-managed wildlife land systems—areas managed primarily for wildlife conservation and nature-based public use – in the U.S. Visit MyFWC.com.

Early Season Hiking Reminders

Early season hiking gear. Photo: MDIFW

Even in May, many of Maine's hiking trails are still covered in ice and snow, especially at higher elevations and in northern parts of the state. Also, roads to get to trails are still quite muddy or even impassable. Maine’s Department of Inland Fisheries and Wildlife’s Warden Service suggests the following reminders to ensure a safe and enjoyable outing:

• Check local conditions - Do your research before heading for a hike. Consider a local trail as you prepare for bigger hikes later in the season.

• Always tell someone where you are going, when you plan to return. Should something happen, this will be key to helping the Maine Warden Service and other search and rescue personnel find you.

• Know that conditions vary significantly across the state and at different elevations. It might feel like spring in southern Maine, but in northern parts and at higher elevations, there is still plenty of ice and snow. Some trails are extremely muddy and closed to prevent trail damage – research your trip before you go.

• Remember that it gets dark much earlier in the spring than the middle of summer. Plan accordingly, and always pack a flashlight in case.

• Dress for the weather and in plenty of layers. Hiking boots with ankle support and tread are ideal. While it’s best to avoid icy conditions altogether, pack a pair of crampons or ice creeper, in case.

• Be prepared for no cell phone service.

• Pack essential items, including high-protein snacks, water, and a fire starter.

• Many roads will likely be impassable due to mud, snow or a combination. Have a plan B, and stick to the places you know are safe. Save your bigger adventures for later in the season.

• Respect the land by picking up after yourself and staying on the trail. Some 94% of Maine's forest land is privately owned and more than half of that land area is open to the public. This access is an incredible gift. To preserve it, we all need to do our part.

Wisconsin Learn to Bear Hunt Seeks Applicants, Instructors

A black bear. Photo: WDNR

The Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources (DNR) is encouraging novice and experienced bear hunters to join the Learn to Hunt Bear program as participants and instructors. The Learn to Hunt Bear program provides a unique learning opportunity and outdoor experience for novice hunters who need a pathway into bear hunting. The program includes multiple classroom and field sessions, culminating with a bear hunting excursion. Participants will learn about bear biology, population management, habits and habitat, hunting techniques, regulations and safety. Anyone who has not previously participated in the Learn to Hunt Bear program or received a bear harvest authorization is encouraged to apply. Participants must be at least 10 years old and lack a pathway to hunt bears, such as bear hunting with family or friends. Interested participants should complete an application and send it to the DNR. The application, program guidelines and more information on the DNR’s Learn to Hunt Bear webpage. The number of Learn to Hunt Bear programs offered varies annually and will influence the number of participants selected. Applicants will be notified of the status of their application by June 1. In addition to participants, WDNR is also looking for groups of experienced bear hunters interested in becoming Learn to Hunt Bear program instructors. Potential instructors need at least five years of bear hunting experience and must consent to a background check. The DNR will work with instructor groups to develop a Learn to Hunt Bear program in their area. Interested groups should notify Emily Iehl, DNR Hunting & Shooting Sports Program Specialist, at Emily.Iehl@wisconsin.gov of their intent to host a program.

UPCOMING EVENTS

Upper Peninsula Trapper’s Association Convention and Outdoor Show - The Upper Peninsula Trapper’s Association Convention and Outdoor Show will be held July 12 - 13, at the Upper Peninsula State Fairgrounds, in Escanaba Michigan. Camping and food are available on the fairgrounds. Demos, mini raffles, can raffles, special entertainment and projects for kids will be held. Demonstrators include by Les Johnson, Paul Antczak (of the History Channel’s “Mountain Men”), Laura & Zac Gidney, Jeff Dunlap and others. Vendor spaces are available. For more information, contact Roy Dahlgren (906) 399-1960 or email trapperroy@outlook.com. Additional information will be available at www.uptrappers.com.

New England Trappers Weekend - The New England Trappers Weekend will be held August 15 – 17 in Bethel, Maine. Contact Neil Olson at (207) 875-5765 – landline, or (207) 749-1179 – cell.

West Virginia Trappers Convention - The West Virginia Trappers Association will hold their 55th Annual Trappers Convention on September 20 - 21, at the Gilmer County Recreation Center, located at 1365 Sycamore Run Road, in Glenville, West Virginia. Admission is free. Gates open at 9 a.m. Friday and 8 a.m. Saturday. A free Trapper Education Class will be held Saturday, Sept. 21, with registration at 8:30 a.m., classes begin at 9 a.m., and lunch at noon and class graduation at 1 p.m. A general membership meeting and awards ceremony will also take place at 1 p.m. Saturday. Benefit Auction will be held at 2 p.m. Saturday. The board meeting will be held Friday at 7 p.m. Primitive camping is available. Also, lunch will available both days in the dining hall. Several events for the women, kids, and more will be held. Trapping demonstrations and vendors will be available both days. For a list of vendors and more information, visit www.wvtrappers.com or contact Jeremiah Whitlatch (304) 916-3329.

What’s Coming in June

Feature Articles

Muskies on DIY Plugs - Phil Goes tries to find a way to fool big muskies on homemade plugs and shares the trials of being a fisherman.

Reading Sign - Pro trapper and TV adventure bowhunter Tom Miranda shares how to get better at reading sign left by game and furbearers.

Helice: A New Shotgun Game - Troy Basso discusses Helice, a new shotgun game, that offers a PhD in wingshooting practice. Here’s what it’s like and how to get involved.

Bike-In Bowhunt For Elk - Scott Turo shares his Oregon bowhunt adventure where he bicycled into the mountains to hunt elk.

Summertime Brook Hoppin’- Wild brook trout and grasshopper fly patterns make a great summertime combo. Chris Ingram shares how to fish them.

Other Stories

• Topwater Bass Busting – Jeffrey Miller looks at topwater baits for largemouth bass and how to fish them

• Eyeshine: Animal Eyes in The Dark – Jeffrey Goddin tells how to determine what critter is what by the reflection of its eyes in a light source.

• Traplines on Big Timber – Chapter 7, Part 1

• Battling The Bite: Ticks, Mosquitoes – Matt Cunningham looks at ticks and mosquitoes and how to handle the problems they create.

• Cougars in the Great Lakes Region: Are They Here to Stay? – Richard P. Smith documents a slew of cougar sightings, shares game camera and other photos and considers if cougars will become part of the Lake States’ wildlife again.

• Streamers For Spring Slabs – Jeremy Grady suggests trying fly fishing, specifically with streamers to catch spring crappies.

• Arctic Grizzly and Caribou Hunt – Tyler Kuhn takes two clients on an Alaskan caribou hunt and encounters grizzlies and caribou.

• The Texas Rig: A Bass Classic – James Hively looks at the past and present of the Texas rig for bass fishing and tells you how to use one.

• A True Dog Story – K. Dwight Milgrim’s tale about a fishing getaway for a trio of farmers and an old hound dog is sure to leave a smile.

End of the Line Photo of the Month

Chad & Tom Guy, Chase, Michigan

SUBSCRIBE TO FUR-FISH-GAME Magazine