Wilderness Adventure: Adirondack Trapline

Wilderness Adventure: Adirondack Trapline

By Toby Walrath

From the day I set my first trap on the muddy banks of the river that flowed through my hometown, I dreamed of a remote cabin in the Far North where I could put up fur as I warmed myself by the woodstove, boiling water for tea. I would share each day’s adventure with a trusted trapping partner, and then read a good book by the lantern glow. My brother, Bud, shared the dream, yet we knew we would likely never make it happen.

But what if we could experience that wilderness trapline a little closer to home? The Adirondack Mountains were right out our back door, and we were fairly certain no one had trapped the area for years. When circumstances finally allowed, we set aside the entire month of November for our adventure—plenty of time to run a trapline that might attain a true wilderness feel.

The Adirondacks offer some of the best trapping in the nation, with abundant beavers and otters in literally hundreds of small lakes and connecting streams. We wanted a place to ourselves, and the largest unbroken wilderness is the Five Ponds Wilderness Area, named for a chain of lakes in the middle of nowhere.

The Oswegatchie River meanders through the boreal woodlands, providing a way in by canoe. Being adventurous, and overly ambitious, we decided to canoe 12 miles to a trail head, portage 2-1/2 miles over a steep moraine, and then paddle across Big Five Lake, where we would establish camp. In hindsight, we could have enjoyed a great experience without the over-land hauling. But we wanted solitude, and the Oswegatchie river is a popular travel corridor for hunters.

After a three-day scouting trip that summer, we agreed on the remote and trailless Big Five Lake. A call to the local forest ranger secured the needed permit for establishing a month-long camp in the coming fall. Permission is required for any stay in the Adirondacks lasting longer than two weeks.

With the campsite chosen, we began making lists and gathering supplies. The chore was more complex than we thought it would be, and after the experience, it is clear that dehydrated potato flakes, pasta, minute rice and freeze-dried veggies should go at the top of the food list and whole grain rice, canned foods and cheese at the bottom, or be eliminated altogether.

Just think “light and easy” when choosing food. By easy, I mean done when you add hot water. Unlike during a leisurely summer camping trip, time to cook can be at a premium when running a wilderness trapline camp.

The final consideration was which traps to bring. Our primary targeted species were beaver, otter and fisher. We also secured permits to trap six marten each. Although marten numbers were not high in the area, the chance to catch them pulled us deeper into the backcountry.

I brought two dozen traps, a mixed bag that included 330, 220, and 110 bodygrips; No. 1-1/2 coilsprings and No. 4 double longsprings.

We decided to bring a half-dozen beaver hoops and a dozen wire stretchers of various sizes, and fleshing tools including a hardwood beam. We could have made a fleshing beam on site by peeling a 6-inch-diameter log, but since my brother was willing to carry it in, I let him.

We set up a spacious tent camp in advance, 200 feet from the water on flat, dry ground that offered a partial view of the lake. We built a wood pole frame to support the tarp roof and walls and then added a lean-to roof out over the door entryway to keep firewood dry and also provide a place for fleshing pelts out of the weather.

Elevated beds were made from small wood poles tightly wound together on frames secured with wire and penny nails. Shelves were built in similar fashion. We made the woodstove out of an old 20-gallon barrel, resurrected from a hunter’s camp of long ago. Sand packed around the bottom and a few new sections of stovepipe funneled the smoke up and out of camp. A latrine was dug away from camp, and firewood put up.

The first day of my wilderness trapline finally came, and I pushed off at the inlet in a 17-foot canoe. My brother would meet me at camp in a day or two. He already had spent several days there but had returned home to get final supplies before settling in for the month.

I paddled silently along the ever-winding Oswegatchie, 75 feet at its widest point. Beavers and muskrats swam beside me; geese winged along overhead, singing their wild song. Several white-tailed deer jumped from the banks when I rounded corners, splashing through the water-logged grass and into the tag alders. Slowly, the wilderness opened before me, and everything else disappeared behind.

The 15-mile journey required an overnight stay, since I didn’t make it to camp before nightfall. I made a simple camp with a tarp and parachute cord then settled into the sleeping bag, eager to get back on the trail at first light.

I arrived at camp the next day, and as soon as I had things organized and put away, I paddled up the creek that feeds Big Five Lake. Beaver lodges dotted the shoreline, and I spotted six river otters bobbing in the lake. I began stringing steel, anticipating a camp filled with drying pelts.

Shortly after returning to camp, I saw Bud in a small pack canoe, making his way across the lake. Bud unloaded then went about organizing traps and splitting wood. He already had been able to stay at camp for 10 days; although it had rained and the wind had blown the entire time, he said he felt fortunate to have enjoyed the extra days. We hoped for drier weather and talked about the possibility of the river freezing before we planned to leave. It was November, and the Adirondacks have little sympathy for travelers.

The only trail out followed the river for 12 miles but had not been cleared since a windstorm swept through years before, leaving the trail largely impassable. Still, it was the only land route, should we need it. We would keep an eye on the weather.

Neither of us wanted to leave early, but we weren’t prepared to stay the entire winter, either.

Soon, the traplines began to produce fur. Bud came in with an otter, and I followed it up with a few beavers. One morning I set out to check my line and found a beaver in a trap I had set in a feeder stream the day before. As I was removing the prime beaver from the trap, I noticed a 330 I had set on a spillway was disturbed. I paddled over and found a large otter in that trap. The next trap, located a few hundred feet up the creek, held another otter.

What a great morning.

As the fur piled up, so did the clutter in camp. Beaver hoops hung from the inside frame poles, and stretchers holding otter and muskrat pelts dangled from a wire stretched across one corner. We didn’t mind working around the pelts, and we helped each other stretch furs tightly while dinner cooked on the stove.

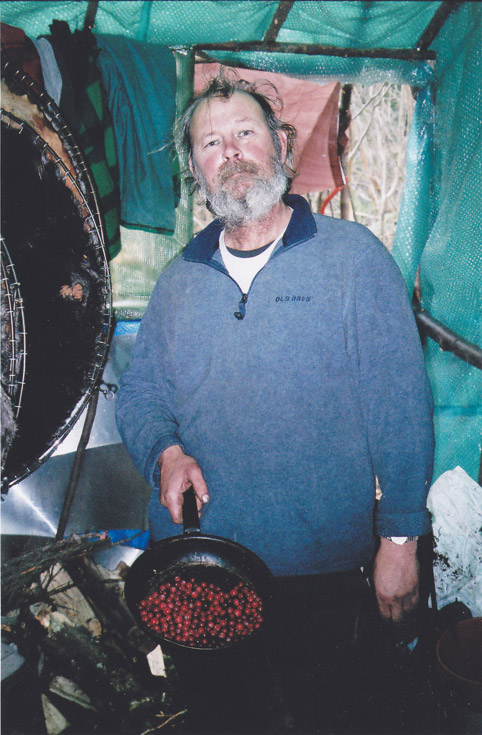

We fried slabs of fresh beaver meat in butter, onions and spices. Mashed potatoes or noodles complemented the meat. We picked cranberries from the bog in front of camp. After softening them in water on the woodstove, we mashed them up and added sugar to make a fine cranberry sauce.

We ate like kings.

It remained unseasonably warm the first two weeks, but then the mercury started to drop. Ice formed around the edges of Big Five, and it became a challenge to get the canoes out to open water. We continued to trap and explore the wild and scenic area with daily forays, returning in the evening to share stories and tend to camp chores before nightfall.

Our solitude was broken when two friends joined us. We welcomed the visitors, as even brothers can wear on each other after weeks alone together. I met Eamonn and Jeff at one of three lean-tos on the way into camp. We had planned for their arrival halfway through the month to get a weather report and so they could hunt deer for a week during the peak of the rut. It was truly enjoyable to have friends take part in the wilderness experience. Eamonn learned how to skin and flesh beaver and shot his first squirrel while at camp.

We hunted deer together during the day. Early morning sits and deer drives filled the days while stories and laughter were shared late into the evening. On the final morning of their stay, Eamonn shot his first buck along the banks of the Oswegatchie, a mature eight-point.

It was his birthday—what a gift.

After our visitors left, Bud and I began the bittersweet task of pulling traps and shuttling gear back to the river. On the final morning of our stay, we dug out the fire pit that had accrued under the stove and poured water over it to be sure it was out. We returned the natural vegetation to the area where our temporary home had been and scattered logs to cover it. The latrine was filled in with dirt, and we respectfully left the area as we had found it.

The fur was placed in plastic garbage bags to keep dry and then fastened to the canoes with rope. Ice was chopped to form a narrow path to get the canoes out into the open water of the lake, and then we made our way back to the outlet and over the steep moraine to the trail leading back to the river.

We arrived at the lean-to on the banks of the Oswegatchie an hour after dark, where we stayed one last night. The wilderness trapline had been hard work, the days long and tiresome. And that’s exactly how I had imagined it would be.

After hiking and canoeing along the trapline all day, I had put up fur and warmed myself by the woodstove as water boiled for hot tea. I had shared each day’s adventure with a trusted partner, and then read a good book by the lantern glow.

Life on a wilderness trapline was no longer a dream, but rather, a truly memorable experience.