Team Fur News - Jun24

Team Fur News - Jun24

Of Fords and Fathers

By FUR-FISH-GAME Editor, John D. Taylor

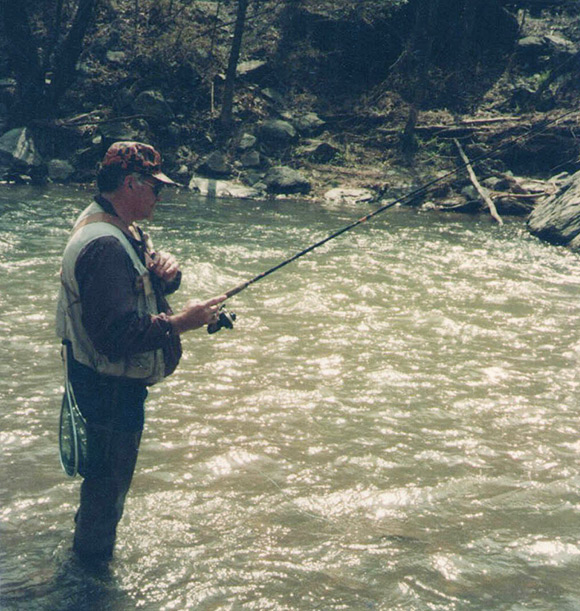

My father, trout fishing on Muddy Creek in the late 1980s.

Mothers, bless them, are critical to the survival of the human race. Without them, we wouldn’t be here. For this, for all the things they do, they deserve enormous thanks and their own special day, celebrated last month. You know, Moms, apple pie and Chevrolets….

Well, I have two questions: What about Fords? What about fathers?

I come from a family of Ford and Lincoln-Mercury drivers. My grandfather, whose middle name I carry, insisted on driving hearse-black Mercury four-doors from the 1960s with tail fins and curb feelers. His “machine” was always perfect, never scratched, never dirty, purred like a kitten when started. The tan upholstery never knew ketchup stains from a fast-food joint. And when he passed away, Grandma Taylor drove that car to church every Sunday – even drove it to see her grandkids over in Dallastown sometimes.

And what about fathers? Fathers get a special day in June. But it doesn’t get the hoopla Mother’s Day does. Advertisers trot out grills, ugly Bermuda shorts and polo shirts, maybe a few fishing rods and bass boats for Dad, but there’s none of the maudlin, weepy-eyed, sentimentality associated with mothers and Mother’s Day for the old man. There’s no “Dads, cherry pie and Fords…” Dodges if you prefer.

Society doesn’t give dads much credit. Historically, fathers were income producers, disciplinarians, fixers of things, family ramrods, cannon fodder for the military, and especially nowadays, they are too often regarded as disposable. When marriages break up, courts usually create single families run by Mom, not Dad.

I think we need to reevaluate our relationship with our fathers. Learn to appreciate them a whole lot more.

My father is gone now, 16 years in early June. Yet it is to him that I owe so many things.

Dad was not a hunter, certainly not a trapper, and only an occasional fisherman. Yet, despite not sharing these passions, he encouraged my early interests and set me on a path that is my heart and soul. For the love of his son, I am indebted, grateful, honored and wish I knew how to return his gifts of time and love, if only to pass them on to another generation.

My father, W. Eugene Taylor, was born in the midst of the Great Depression and grew up in the 1940s and 50s in Red Lion, Pennsylvania, one of many small towns in the southcentral part of the state.

His home – the Taylor family homestead – was on the edge of town. It spawned several generations of Taylors and was created when there was barely any Red Lion at the turn of the previous century. A railroad track and a grain mill ran south of the house. Beyond that was what Dad and his pals called “Apache Territory,” woods, fields, and creeks where kids could play and explore.

As a kid, he did all the things kids did back then. He told stories about hating to weed the humungous family garden below his home, about how he and my grandfather shot rats in the small barn behind the house with a .22 when they got into the chickens’ feed, about dropping water balloons on cars passing under a railroad trestle with friends, and pushing over some outhouses (indoor plumbing made them obsolete) while hanging out with n’er-do-well buddies.

My father developed a real passion for football as a kid. He wanted to play, but Grandma, worried about him getting broken bones or worse, and said no. (Protective gear back then wasn’t what it is today.) The closest he got to the gridiron was playing trombone in the high school marching band. That’s where he met my mother. Football would play a prominent role later in his life, though.

He graduated from high school, worked, and in the late 1950s, served in the Army, in Germany, as a musician. When he returned from Germany, he married my mother. Together, they brought my sister and me into the world in the early 1960s.

Dad worked in various elements of the construction business over his lifetime. One job was with a professional painter, Everett Gemmill, skills he would later share with me when I came to own a home. He worked for his father-in-law’s construction business, where he fell down a ladder from a roof on a church they were building. He never complained about permanent damages, but Dad was always stoic. Sears’ Home and Garden Center was his employer for a time. He eventually became a construction estimator, working for several different outfits in that industry’s tumultuous economy from the 1970s through the mid-1990s. He retired from a state construction estimating job in early 2000s.

After my sister was born my family relocated from Red Lion to a home above the Dallastown High School in what was then a tiny suburban development. This allowed easy access to the Friday night football games played on the high school field. At one of these games, probably in the late 1960s, Dad, Lonnie Barnhart and Mervin Slenker were sitting in the bleachers, watching Dallastown’s losing team get creamed – again. I sat beside Dad. He said they ought to do something to improve the team. The other two adults agreed.

That conversation morphed into the Dallastown Midget Football Association, where three age groups of kids got a chance to learn how to play football and improve their skills. My father was the driving force behind making this real. He had the help of a community who shared his goal, along with key people to serve as coaches, referees, equipment managers, etc.

The impact of this was significant. By the time I graduated from high school in the late 1970s, Dallastown’s football teams went from their last place standings before midget football to state and regional champions. Yet Dad hardly got any credit for this, high school coaches did. I thought that was unfair.

I wish I could have shared my father’s love of football, if only to honor him. But being a chubby kid, who didn’t run fast and had his passions elsewhere, that just didn’t happen. The traps my grandfather gave me for Christmas when I was 12 sent me along another path.

As a kid, I was always more of a night owl than an early riser. Yet when I had traps set, I managed to get up at 5:30 a.m., dress, creep over to my parent’s closed bedroom door, knock gently, open the door and hesitantly whisper, “Dad, it’s time.”

There was a groan, but Dad got out of bed, dressed and hauled me in his yellow Javelin to where my traps were set so I could check them. I didn’t understand the ramifications of this until much later in life, when bird dogs and horses and adult responsibilities busted my slumber at 5 a.m. How my father managed to do this, work a job, then come home and face teenagers and the demands of family life in the 1970s, blows my mind.

Pennsylvania game laws prohibited me from hunting alone until I was 16. Having developed a passion for small game hunting – think pheasants – Dad was obligated to take me hunting for that, too. Problem was, Dad hated small game hunting. A bad experience with a landowner when he was younger soured it. He shot a pheasant on land he could legally hunt, but the bird landed across the landowner’s fence. When he went to fetch the bird, the landowner wouldn’t let him cross, gave him grief. Although I knew that, I still didn’t appreciate the extent of Dad’s gift in taking me pheasant hunting then. I do now.

When I turned 16 and could drive, his hard-labor sentence with pheasant hunting ended, but a new trial began – teaching his son to drive. Dad had a cool 1975 Ford Bronco then, blue with a white top. Driving scared me at first, but I got the hang of it. Dad’s mostly taciturn way was far better than my mother’s technique. In her car, a Ford Granada, when we traveled through the narrow streets of Dallastown, she’d brace for impact, put her feet on the dash and say, “Watch… Now watch, watch, WATCH!” every time another car passed.

Dad did go deer hunting, but I suspect it was more to hang out with family – a cousin owned the Potter County, Pennsylvania, deer camp we hunted from for three decades – than his interest in tagging a buck. He never fired his .35 Remington Marlin lever rifle at a deer that I knew of. But he enjoyed the solitude and peace of the mountains, until his heart condition stymied climbing those steep hillsides.

That’s probably why he talked my mother into buying “Many Pfennings,” their own cabin in Michaux State Forest, near Chambersburg, Pennsylvania. It started out as a musty, outdoorsman’s retreat, a place that had hosted hunters and anglers. Mother rehabbed the interior into a home-like setting, with fancy curtains, new cookware, re-done cabinets, furniture, and way too many air fresheners. Dad helped, sprucing up the interior with painting and carpentry work, repainting and staining the exterior.

The evolution of the place kinda bugged me. In becoming a mini-Dallastown, like their home, it lost its cabin charm. But it was located in a world where I learned how to hunt ruffed grouse and where, eventually, four treasured gun dogs would have their final rest.

I tried to get Dad interested in spring gobblers from the cabin, but our single outing was unproductive. I heard the gobbler hollering down over the hill, Dad didn’t. And 75 degrees wasn’t hunting weather, he said.

In the early 2000s, I tried, in my own dumb way, to do something special for my father. We went on mid-winter combination deer and quail hunting trip to Alabama. We’d stay at a fancy lodge in the Black Belt region, hunt deer together – something we hadn’t done for a while – and I’d hunt quail for an article I was writing. I asked the lodge owner to help my father get his first deer, since he’d never tagged a Pennsylvania buck. (He claimed to be holding out for a big buck.)

The first day, we hunted together from a very cold (17 degrees, unusual for Alabama) deer blind without seeing any bucks. I tried to get him to come along for the quail part, but he had no interest in it.

On the final day, the lodge owner and my father shared a blind, while I was in a separate location. When I returned, the lodge owner said Dad had been successful, taken an old management buck. I saw the deer, a nice buck. Happy for Dad, I asked for the story. A short tale about spotting the deer and taking the shot followed, with little excitement. I always wondered what really happened. Did Dad tell the lodge owner he was there to spend time with his errant son, not shoot a buck, so the owner took a cull deer and called it Dads?

Dad passed away alone, working on the cabin that had become his refuge. I asked my mom about the deer, but he'd apparently never told her the story, so it remains a mystery. My father’s love for his family was no mystery. We all felt it.

Treasure the fathers in your life. They are gone far too soon.

Leave Young Wildlife Alone

Wildlife officials say to leave what appears to be orphaned wildlife alone. Photo: MDC

Wildlife agencies across the nation are urging well-meaning people to leave any young wildlife they encounter alone. While some young animals might appear to be abandoned, usually they are not. It’s likely their mothers are watching over them from somewhere nearby. For example, when encountering young wildlife, the best thing you can do is leave it alone, says the Pennsylvania Game Commission’s Wildlife Management Director Matthew Schnupp. Adult animals often leave their young while they forage for food, but they don’t go far, and they do return. Wildlife also often relies on a natural defensive tactic called the “hider strategy,” where young animals will remain motionless and “hide” in surrounding cover while adults draw the attention of potential predators or other intruders away from their young. Deer use this strategy, and deer fawns sometimes are assumed to be abandoned when, in fact, their mothers are nearby.

“During the summer,” said Jenna Fastner, Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources captive wildlife health specialist said, “we receive many inquiries from concerned residents about the wildlife they are encountering while camping, hiking or even in their backyard. “While touching a young wild animal does not cause the mom to reject it, human scent can give away its location to a predator and risk the animal’s health. In addition, contact with a wild animal can also put your health at risk. Always contact the DNR or a licensed wildlife rehabilitator for advice before intervening.” Wild animals carry many diseases and parasites, including some that can spread to domestic animals and humans. “Young animals are rarely orphaned,” said Missouri Department of Conservation (MDC) State Wildlife Veterinarian Sherri Russell. “When we see newborns alone, that means the parents are likely out searching for food and will return. If you see a chick with feathers hopping on the ground, leave it alone because it’s a fledgling and its parents are nearby keeping watch. Fledglings can spend up to 10 days on the ground learning to fly. If you find one that has no feathers, it likely fell out of its nest, and you can return it to the nesting area if possible.” Another animal Russell warns against interfering with is young rabbits.

"Rabbits seldom survive in captivity and can actually die of fright from being handled,” she explained.

Finally, it’s typically illegal to possess what appear to be orphaned wild animals, despite the best of intentions. In Pennsylvania, a fine of up to $1,500 per animal could be levied. Only licensed wildlife rehabilitators are permitted to care for injured or orphaned wildlife. A listing of licensed wildlife rehabilitators in Pennsylvania can be found at www.pawr.com, or call 1-833-PGC-WILD or 1-833-PGC-HUNT. In Wisconsin, a list is available via https://dnr.wisconsin.gov/topic/WildlifeHabitat/directory. Visit https://dnr.wisconsin.gov/topic/WildlifeHabitat/orphan for more information about whether wildlife is actually orphaned or not.

Minnesota’s CWD Management

Most of Minnesota’s CWD cases are coming from the southeast corner of the state, MDNR says.

Chronic wasting disease remains relatively rare in Minnesota, according to the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources (MDNR) and the state needs hunters’ help to keep it that way. CWD was detected in 43 hunter-harvested deer during the 2023 hunting seasons. Of these, 91% were from the southeast, a region that continues to see persistent CWD infections in wild deer. MDNR’s CWD surveillance found one positive deer in a new deer permit area, all other positive cases were found within existing CWD management zones. Targeted culling. MDNR says, is a management tool used to slow the spread of CWD where it is known to exist. MDNR does not cull deer across broad areas but will cull within 2 miles of a known positive location. All culling is conducted with landowner permission. Of the total CWD-positive deer found in Minnesota since 2010, nearly 30% were removed through culling efforts. All MDNR culled deer are processed by a licensed meat processor and the venison is stored until test results are received. Deer that receive a “not detected” test result are given back to participating landowners or donated to food banks for distribution to local food shelves. Deer that test positive are disposed in an alkaline digestor.

For more information about Minnesota’s CWD efforts visit mndnr.gov/cwd.

West Virginia State Record Bowfin

Lauren Noble caught and released a 10.60-pound, 30.20-inch bowfin,

a new West Virginia record. Photo: WVDNR

The West Virginia Division of Natural Resources (WVDNR) acknowledged an angler caught a state record bowfin from the Ohio River in Mason County. The fish is the fourth state record catch confirmed since December 2023. The record fish, a 10.60-pound, 30.20-inch bowfin, was caught and released on March 12 by Lauren Noble from Letart, in Mason County, using a small crankbait. Noble’s record bowfin was certified by WVDNR District 5 fish biologist Jeff Hansbarger. Noble’s record-breaking catch comes less than a week after a state-record redbreast sunfish and tiger trout were caught at New Creek Lake. A record blue catfish also was caught on the Ohio River late in 2023. Noble’s catch surpasses the previous weight record holder, a 9.25-pound bowfin caught by Matt Stender in 2006. Donald Newcomb III continues to hold the 32.25-inch length record he established in 1994. Learn more about state fish records at WVdnr.gov/fishing-regulations.

Shed Hunter Kills Montana Grizzly

Grizzly bears are now found anywhere west of Billings in Montana. Photo: Becca/Unsplash

A man searching for shed antlers shot and killed a grizzly bear on April 25 during an encounter on private land northwest of Wolf Creek, Montana, according to Montana Fish, Wildlife & Parks (MFWP). The man was walking along a ridge covered with low trees and brush with his two dogs at his side and the wind at his back while searching for shed antlers. After seeing a fresh grizzly bear track in a snow patch, he continued along his path and a few minutes later he first saw the bear standing near the top of the ridge about 20 yards away. The bear dropped to all four legs and charged. The man drew his handgun and fired five shots from distances about 30 feet to 10 feet, grazing the bear with a one shot and hitting and killing it with another shot. The man was not injured in the encounter. He was not carrying bear spray. The adult female grizzly was in good condition weighing around 300 pounds and was estimated to be 12 years old. The bear had a single cub-of-the-year nearby. The cub was later captured by MFWP bear management specialists and taken to MFWP’s wildlife rehabilitation center in Helena. The incident remains under investigation by the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service. With spring, bear activity is increasing in Montana. MFWP says bear aware habits can prevent conflicts. Grizzly bear populations continue to become denser and more widespread in Montana, increasing the likelihood that residents and recreationists will encounter them in more places each year. Grizzly bears remain a federally protected species under the Endangered Species Act. Avoiding conflicts with bears is easier than dealing with conflicts. MFWP encourages all outdoor people to learn about bear safety and the effective use of bear spray. Visit fwp.mt.gov/bear-aware

You Get A Free Book! And YOU Get A Free Book!

Order any FUR-FISH-GAME merchandise in the month of June and get a free copy of the classic Harding trapping book, Fox Trapping, by A.R. Harding. That's it. No catch. If you order over the phone be sure to mention you saw it here.

Penn State’s ‘Venison 101’ course

Penn State University is offering a course to help hunters turn their deer into the

best venison possible. Photo: Alex Munsell/Unsplash

Penn State’s Extension is offering an updated “Venison 101” course to help hunters optimize their harvest. The course combines online components with an in-person workshop scheduled for 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. Friday, August 23, at the Penn State Meat Laboratory on the University Park campus in State College, Pennsylvania. This course is designed for hunters and hunting families. “We had a number of requests for online information about hunting, field dressing and processing during the pandemic,” said Catherine Cutter, professor of food science in Penn State’s College of Agricultural Sciences. Seeing the need for online resources apart from standard publications, Cutter and her team transformed “Venison 101” into a hybrid course with online materials and in-person activities. The online components will cover the history of hunting and deer ecology, field dressing, deer diseases, chronic wasting disease, carcass processing, recipes, and home food preservation of venison using methods such as canning, dehydration/jerky making and freezing. The in-person workshop will include hands-on processing of carcasses, sausage making, venison tasting and a chili cook-off. More information is available on the Penn State Extension website at https://extension.psu.edu/venison-101-hands-on-butchering-processing-and-cooking or by calling 1-877-345-0691.

Texas Wildlife Impacted by State’s Largest Wildfire

The Smokehouse Creek Fire destroyed more than 1 million acres in Texas’s Panhandle

region in March. However, biologists expect wildlife and the ecosystem to bounce back.

Photo: Texas A&M AgriLife Extension Service

Humans and domestic animals weren’t the only residents facing danger and displacement as flames from the Smokehouse Creek Fire roared across Texas’s Panhandle in March, consuming more than 1 million acres. Wildlife populations were also affected by the historic wildfires. However, Texas A&M AgriLife Extension Service experts are optimistic about the recovery, focusing on the long-term positive ecological response following the fire that benefit wildlife. It’s important to recognize that native wildlife and vegetation have evolved alongside fire for millennia, said Jacob Dykes, Ph.D., AgriLife Extension wildlife specialist. Historically, these fires were caused by lightning strikes and other natural events.

“In most cases, wildlife can sense fire danger and escape,” Dykes said. “For example, deer and pronghorn antelope can smell and see a fire coming, so they know to run. Birds will fly to safe areas, and burrowing animals will retreat to underground dens.” However, the Panhandle fires were an “unprecedented” event with a widespread impact, Dykes said. The wildlife expected to be most affected were white-tailed deer, raccoons or other smaller mammals. Since the fires occurred prior to nesting season for ground nesting birds, like quail and turkeys, they probably avoided widespread damage. Also, since fawning season for deer and pronghorn, hadn’t started there was less damage there. One heavily damaged area was Texas Parks and Wildlife Department’s (TPWD) Gene Howe Wildlife Management Area, along the Canadian River. Of the 5,394-acre WMA more than 5,100 acres of the midgrass rangeland and mixed cottonwood and tallgrass bottomland burned. Yet Chip Ruthven, TPWD project leader for Panhandle WMAs, said he and others have encountered a promising number of surviving wildlife on the property including deer, turkey, quail and a variety of songbirds. He attributes this to pockets of unburned rangeland scattered throughout the burn that provided a refuge.

Cover for ground nesting birds may be limited this spring, but given adequate rainfall, should improve by early to midsummer, Ruthven said. Biologists will have to wait until trees leaf out to assess the fire’s impact on riparian zones adjacent to the river. Ruthven and other biologists believe the Howe WMA’s response will be similar to the recovery following the East Amarillo Complex fire in 2006. Before the Smokehouse Creek Fire, the East Amarillo Complex fire was the largest wildfire in Texas history, burning more than 900,000 acres. “Like the mythological phoenix, we anticipate the rangelands and wildlife of the Panhandle will rise from the ashes and flourish like it did following the fire in 2006,” Ruthven said. “Fire rapidly breaks down the nutrients in vegetation and delivers them to the soil,” Dykes said. “If the area has sufficient precipitation afterward, there will be a great response from grasses and herbaceous flowering plants sooner rather than later.” This resprouting vegetation will contribute to species diversity, leading to a variety of wildlife cover on the landscape. Additionally, this new vegetation will provide nutrient-dense forage and browse for species ranging from insects to large mammals.

Grand American Trapshooting to continue in Illinois

The Grand American trap shoot will continue to be held

at the World Shooting and Recreational Complex in Sparta, Illinois, through 2036.

The Illinois Department of Natural Resources (IDNR) and the Amateur Trapshooting Association (ATA) have signed a contract extension that clears the way for the World Shooting and Recreational Complex in Sparta, Illinois, to host the ATA Grand American through 2036. “I’m thrilled we were able to extend this contract for another decade,” said IDNR Director Natalie Phelps Finnie. “The ATA Grand is a premier event and an important economic driver for Randolph County and southern Illinois. It’s a privilege to host the Grand at the World Shooting Complex, and we look forward to continuing our strong partnership with the ATA.” The Grand American, the largest and oldest shooting event of its kind, features more than 20 events and attracts more than 5,000 competitors and spectators from across the globe annually. The event, which was first hosted at the World Shooting Complex in 2006, has an estimated economic impact of $25 to $30 million annually. The 2024 Grand American is set for July 31 to August 10. More than 4 million targets will be thrown during the event. The World Shooting and Recreational Complex in Sparta is an IDNR site. The 1,600-acre complex is open to the public Wednesday through Sunday each week. Activities include trap and skeet shooting, sporting clays and other sporting activities. The site also features more than 1,000 campsites and fishing opportunities. Visit https://dnr.illinois.gov/parks/worldshootingrecreationalcomplex.html

Emerald Ash Borer in Washburn, Taylor Counties

An emerald ash borer. Photo: WDNR

The Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources (WDNR) has detected emerald ash borers (EAB) for the first time in Washburn and Taylor counties. Burnett is now the only county without a detection since EAB was first discovered in Wisconsin in 2008. WDNR staff members collected larvae samples in Springbrook and Medford. The U.S. Department of Agriculture confirmed these larvae were EAB. The detections will not result in regulatory changes because EAB was federally deregulated on Jan. 14, 2021, and Wisconsin rescinded its statewide quarantine effective July 1, 2023. EAB will continue to spread in northern Wisconsin, significantly impacting the state’s ash resource. For those looking for treatment options, the University of Wisconsin-Madison’s EAB webpage (https://eab.russell.wisc.edu/) provides information on insecticide treatment for ash shade trees. WDNR, the state Department of Agriculture, Trade and Consumer Protection, the University of Wisconsin-Madison Extension and tribal partners continue to track EAB’s spread. Detection information aids in EAB readiness planning, management and biological control activities. With 66 new municipal detections already reported in 2024, the map updates continue to occur regularly.

370 Illinois Bobcats Harvested

Some 370 bobcats were harvested by hunters and trappers in Illinois

during the 2023-24 season. Photo: Liz Guertin/Unsplash

When the 2023 - 2024 Illinois bobcat season concluded February 15, 370 bobcats harvested by hunters and trappers. A total of 214 (55%) of the bobcats were taken by hunting. Trapping accounted for 156 (40%) of the harvest. Nineteen (5%) were salvaged by permit holders from circumstances such as roadkill. Hunters and trappers in Jo Daviess County reported 19 bobcats – the most for any county this year. There were 7,000 bobcat lottery applicants in 2023 and 1,000 permits issued for the season. The bobcat harvest from the 2022-2023 season was 367, with 16 salvaged. The Illinois Department of Natural Resources continues to monitor the status of bobcats and will evaluate the program as new data becomes available from ongoing research Visit https://dnr.illinois.gov/hunting/furbearers.html for more information about bobcat hunting and trapping in Illinois.

Upcoming Events

New England Trappers Weekend - The New England Trappers Weekend will be held August 15 – 17 in Bethel, Maine. Contact Neil Olson at (207) 875-5765 – landline, or (207) 749-1179 – cell.

West Virginia Trappers Convention - The West Virginia Trappers Association will hold their 55th Annual Trappers Convention on September 20 - 21, at the Gilmer County Recreation Center, located at 1365 Sycamore Run Road, in Glenville, West Virginia. Admission is free. Gates open at 9 a.m. Friday and 8 a.m. Saturday. For a list of vendors and more information, visit www.wvtrappers.com or contact Jeremiah Whitlatch (304) 916-3329.

What’s Coming in July

Features

Urban Fishing - Phil Goes and his sons explore downtown Green Bay’s fishing opportunities and are surprised by what they find.

Pronghorn, With A Peruvian Assist - Mike McTee and his father DIY hunt Montana’s pronghorns and get help from an unusual source.

Crossbows: Controversy, Myth and Pointers - Heath R. Curtis explores the controversies, myths and offers some pointers for getting better acquainted with a growing deer hunting tool.

An Alaskan Moose Adventure – When Wyoming’s James Phelps fails to draw his moose tag, he gets a surprise offer to try moose hunting in Alaska.

Passing On Trapping’s Heritage – When Jim McCarrick helped with New York state’s DEC trapping camp for kids, he had a great experience sharing trapping with the next generation.

Other Stories

Possibles Bag For Today’s Traveler – Joel S. Brodkey explores a traveler’s necessities in a modern possibles bag.

Turning Fur Into Fish – Curt Walters and friends use fur checks to fish for saltwater species in Florida.

Topwater Smallmouth Summer Action – Glen Walker tells how to catch smallies on topwaters.

Lew & Charlie – Ch. 7, Part 2 & Ch. 8 (the completion of “Traplines on Big Thunder”)

Tailwater Catfish – Ron Peach shares how to catch catfish from these productive waters.

911 Tree Rats: Distress Calling Squirrels – Phil Goes shares a squirrel hunting adventure that includes using distress calls to attract squirrels

A Civilized Hunt – Robert Cates shares things he learned from his father about what represents a “right civilized” hunt, and explores variations on that theme.

Stream Smallmouths – Bruce Ingram tells how to catch bronzebacks from small streams on a fly rod or spinning gear.

Fishing With Papaw – Stanford Fleming, Jr. Shares a touching story about fishing with his grandfather and his experiences in Iraq.

End of the Line Photo of the Month

David Hall, Saxonburg, Pennsylvania

SUBSCRIBE TO FUR-FISH-GAME Magazine