Team Fur News - Feb25

Team Fur News - Feb25

On Thin Ice

By FUR-FISH-GAME Editor, John D. Taylor

Ice fishing? Not gonna happen for this cowboy. Photo: Mike Cox/Unsplash

Our fishing columnist, Vic Attardo, doesn’t understand why I refuse to go ice fishing, given all the comfort items an ice fisherman has available these days.

Why just the other day, Scheels sent me a huge catalog with all sorts of ice fishing gear in it – augers (they’d make great fence post hole diggers) for $300, ice fishing parkas and jackets for another $300 each, ice fishing electronics, tip ups, pack boots, ice fishing tents, heaters, etc. Why for just a couple thousand dollars I could get totally ice rigged, sit over a little hole or two in the ice in sub-zero weather with a 40-mph wind rattling the ice fishing tent and wait for something to bite.

Not going to happen.

How come, you might ask?

First, there’s my general philosophy towards the outdoors. Remember those T-shirts and social media memes about the two tired-looking buzzards sitting on a tree limb? One says to the other, “Patience my (rump), I’m gonna kill something.”

Well, that’s been my philosophy for a long time.

I cannot, for example, imagine myself having the patience to make like a squirrel, sit in a tree stand all day long, waiting for a shot at a deer. Nope, I’d much sooner still hunt or slide across the prairie and encounter deer on their own terms, on the ground, doing something, rather than waiting for action to happen. That’s far more challenging and fun to me. Call me a go-to hunter and angler, not a sit-and-wait guy.

Turkey hunting often strains my patience to its limits. Unless I have birds working towards me, I’m running and gunning, seeking birds, not waiting around for something to happen. I admire the level of patience some turkey hunters have, especially in the East. A guy willing to sit in a blind in front of decoys all day for a single opportunity at a gobbler is pretty impressive – or lazy, or nuts, by my standards. I couldn’t do that. I’d go mad, especially if there were other gobblers sounding off nearby. “Patience my rump...”

Same for fishing. Trout fishing, fly fishing in particular, is more like trout hunting than waiting for something to bite. You go to the fish. Bass fishing, practiced from a boat, is basically the same thing. You hunt lunkers, using likely fish-holding habitat – and nowadays a ton of electronics, like forward-facing sonar (seems like cheating to me) – to determine where to chuck a lure. You’re always reeling, doing something. Same with many other types of open water fishing. It's not a passive endeavor.

Trapping certainly isn’t passive. You make sets where you think a critter is going to be. Then it’s like Christmas morning checking the trapline. I love that analogy.

I have the patience to make sure all my reloaded ammo – and that’s pretty much everything I shoot any more – centerfire rifle, pistol and shotshells – are the best I can make them. I have the patience to trickle precisely 53 grains of Vihtavuori N160 into my primed Hornady .25-06 cases, no more, no less. I have the patience to make sure the 100-grain Nosler Ballistic Tip bullet is seated perfectly. I have the patience to check my .38 Special Cowboy Action reloads so they COAL is 1.47 inches, no more, no less. I check them twice.

For nearly 40 years I’ve had the patience – mostly – to work with bird dogs, particularly the sometimes very stubborn English setters who insist on doing things their way. Same with horses. I have the patience to work them in a round ring, using leg pressure to turn right or left, or thread the needle through a cone set-up in an arena.

Sorry Vic, I simply don’t have the patience to park my keester over a hole in the ice for hours on end and wait for a fish to bite. I do have the patience, and the good sense to wait until spring, when the water opens up and you can do real fishing, not that ice stuff.

Why?

I tried it once. Been there, done that, got the T-shirt. And like a visit to Disney World, I ain’t going back.

Back in early 1970s, when I was teenybopper, two neighbor kid friends down the road invited me to join them and their parents for a mid-winter trip up to Bradford County, Pennsylvania, to visit their grandfather, Bernard McKernan. He was a big-time (at least to me) trapper, and I jumped at a chance to learn something more about trapping because I was a neophyte, anxious to expand what little experience I’d accumulated.

Bradford County is in Pennsylvania’s big mountain country, the northern tier, heavily forested with many creeks in the mountain valleys. The drive north took about four and a half hours, through country I’d not seen before. Since it was midwinter, snow covered the slopes, yet the creeks – freestoners I’d come to fly fish later in life – flowed open and sparkling. It was a wonderland to a kid.

The McKernan home was an older, two-story, white house, a lot like my grandparents’ home down in the flatlands of Red Lion, Pennsylvania. Mr. McKernan, learning I was a trapper, took us up into the attic, to show off his season’s pelt collection hanging from brown-aged early 20th century rafters. There were muskrats, many mink, plenty of coons, and some foxes, all beautifully handled, still taut on stretchers, like I’d seen in photos of how to properly handle furs. The rich aroma of those pelts, warm and meaty, filled my nostrils.

Later, my friends, Scott and Chris Deardorff, and I fell into the winter wonderland. I took my very first snowmobile ride with them, squinching into a snowmobile suit, then zipping across the white faster than I could ever ride a bicycle down the biggest hill back home.

The next morning, Mr. McKernan took us to check his traps. Wintergreen scent permeated the cab of his older-model Chevy pickup on the way to his trapline, the four of us squeezed across the bench seat. The first stop was a small creek culvert, some empty coon and mink sets that he re-lured. Lacking hip boots, we couldn’t follow him up the valley to check other sets, but I won’t forget the image of that tall, white-haired gentleman with a packbasket on his back, ball cap on his head, the Woolrich plaid coat, walking up the creek bottom.

That evening, after dinner, he asked if we wanted to go fishing. Mr. McKernan needed more trapping bait, smelt, he said, and we could catch some from a nearby lake. I wondered how we’d fish on a frozen lake, not having encountered ice fishing before, but it seemed like a grand adventure.

Out across the ice, in the black darkness of the mountain night, we went. The ice had some meltwater on top of it – probably the result of the sunny, January thaw days we brought up from the southern end of the state – and, as kids will do, we slipped, slid and slopped across it with glee.

At a chosen location in mid-lake, Mr. McKernan stopped and began drilling a hole with his hand-cranked ice auger. When that hole was punched, he drilled several others and soon all four of us were perched over a hole, watching a mealworm baited tip-up or holding a short ice rod, waiting for smelt to bite.

Being a kid, proper winter gear like warm wool was not available to me. Too expensive when I’d grow out of it soon, my folks said. Nope, I was wearing what Dallastown kids did in winter. Blue jeans, cotton long johns, a flannel shirt, a blue winter coat stuffed with some sort of man-made fiber as insulation, a knit beanie to keep my ears warm, and thin gloves. Footwear included cotton socks under green rubber boots with yellow laces and yellow “fluff” inside.

All this was fine and dandy if you were goofing around building snow forts outdoors for an hour or two or helping your father shovel snow. But if it got wet, or you were out longer than a couple hours, you’d freeze.

Naturally, being a kid, I’d soaked the blue jeans going out, the yellow fluff inside my boots was all matted down and no longer offered any insulation, and in the black of night the lake picked up some wind, further dropping the already frigid temperatures.

So, there I stood, over that tiny hole in the ice, freezing my cookies off, waiting for some minuscule oily fish to bite. I doubt I could have felt a smelt nibble, my hands were so cold. Those wet blue jeans froze solid against my shivering legs, and in the rubber boots, my feet were icicles. But I was determined to gut it out, not to break and run for the shelter of the truck. No wimping out.

After what seemed like days of waiting, after everyone else caught a few smelt, Mr. McKernan said it was time to go home. We returned to his pickup, ice crackling from my frozen pants as we walked back to the truck in the dark.

By the time we got back to the house, I no longer felt hypothermic. Crawling into my sleeping bag that night, I warmed and drifted off into dreams of what it would be like to have a big trapline, with many pelts hanging in the garage at home. I’d use those mustard covered sardines in cans, not smelt, for bait. (I probably ate more of those sardines than the coons I was after ever did.) I couldn’t blame Mr. McKernan for a not-so-great introduction to ice fishing. It was simply not having the right gear for the circumstance. I’d violated the Boy Scout motto of being prepared.

I’ve been in far colder circumstances – deer hunting in Pennsylvania’s cold, wet mountains; and out here on the prairie as an adult, where even being smothered in layers of fleece, wool, down, windbreaking nylon, two pairs of gloves and stout pac boots didn’t keep genuine frostbite off my fingertips. Feeding horses in 56-below wind chill temperatures will do that.

Nope, what got me was the waiting. A forlorn hope that something might happen, when to me it would be better to make it happen.

So don’t bother to ask me about going ice fishing. You enjoy it all you want. Me, I’m going coyote hunting, turkey scouting, taking the dogs for a run – anything that involves doing, moving, being. Patience my rump...

New Opportunities at National Wildlife Refuges

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) finalized rulemaking permitting hunting and sport fishing on 211,000 acres previously not open in the National Wildlife Refuge System.

In November, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) finalized rulemaking permitting hunting and sport fishing on 211,000 acres previously not open in the National Wildlife Refuge System. Twelve national wildlife refuges in Kentucky, Louisiana, Nebraska, North Dakota, South Carolina, Texas, Washington, West Virginia and Wisconsin managed by FWS, are opening and expanding opportunities for hunting and fishing. This includes first-ever hunting opportunities on Green River National Wildlife Refuge, expanded waterfowl and archery deer hunting on newly acquired acres at Bayou Teche National Wildlife Refuge and expanded fishing on Horicon National Wildlife Refuge.

“Hunting and fishing opportunities within the National Wildlife Refuge System connect people with nature,” said FWS Director Martha Williams. “We are pleased to expand access and offer new opportunities on national wildlife refuges that are compatible with the refuge’s purpose and are committed to responsibly managing wildlife health and these areas for the benefit of future generations.” Hunting, fishing and other outdoor activities contributed more than $394 billion to the nation’s economy across the United States in 2022, with hunters and anglers accounting for over $144 billion of this, according to FWS’s National Survey of Fishing, Hunting and Wildlife-Associated Recreation. The survey also found that, in 2021, an estimated 39.9 million Americans over the age of 16 fished and 14.4 million hunted. The final rule includes requirements to use lead-free ammunition for elk hunting at four refuges in North Dakota and for all hunting on the Big Cove Unit of Canaan Valley National Wildlife Refuge in West Virginia. FWS says the best available science indicates that lead ammunition and tackle can have negative impacts on wildlife. In conjunction with other stakeholders, FWS is engaged in a deliberate, transparent process of evaluating the future of lead use on FWS lands and waters. In the interim, FWS won’t allow any increase in lead use on FWS lands and waters. A complete list of now open to hunting and fishing is available at www.fws.gov.

Snowmobile Safely

Michigan and Wisconsin DNRs are urging snowmobilers to think safety before riding this winter. Photo: MDNR photo

The Wisconsin and Michigan Departments of Natural Resources are encouraging snowmobilers to keep safety at the forefront of their preparations. This includes staying alert to the rapidly changing ice conditions commonly found in the early and later parts of winter. “The biggest thing we want folks to remember is that no ice is completely safe,” said Lt. Jacob Holsclaw, Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources (WDNR) off-highway vehicle administrator. “On a sunny day, ice that may have been thick enough to drive on in the morning may be unsafe by the afternoon, especially during the early part of the season.” This rule also applies to ATVs and UTVs. Last season, several ATVs and UTVs went through the ice, with two resulting in fatalities. Local fishing clubs, outfitters and bait shops are the best sources for current ice conditions. WDNR also encourages all snowmobilers to take a safety education class. By Wisconsin law, anyone at least 12 years of age and born after January 1, 1985, must have a valid safety education certificate to operate a snowmobile. Over in Michigan, home to 6,000-plus miles of Michigan Department of Natural Resources (MDNR)-designated snowmobile trails, public roads and public lands where riding is authorized, MDNR urges snowmobilers to get their $52 trail permits and to Ride Right — sober, at safe speeds and on the right side of the trails. (Visit Michigan.gov/RideRight). Learn more at Michigan.gov/Snowmobiling.

Eastern Hellbender, Monarch Butterflies, considered for ESA

Monarch butterflies roosting in a tree. Photo: Mike Budd/USFWS

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) is looking at adding two species, the monarch butterfly and the Eastern hellbender, as endangered or threatened species under the Endangered Species Act (ESA).

Eastern hellbenders, North America’s largest salamanders, growing as long as 29 inches, can live 30 years and spend their entire in water, in streams and rivers of the eastern and central United States. These amphibians play a crucial role in maintaining healthy freshwater ecosystems. They’re found in Alabama, Georgia, Illinois, Indiana, Kentucky, Maryland, Mississippi, Missouri, New York, North Carolina, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Tennessee, Virginia and West Virginia. Historically, Eastern hellbenders were documented in 626 populations. Recent data shows only 371 of these populations (59%) remain, with only 45 (12%) are stable, 108 (29%) have an unknown recruitment status, and 218 (59%) are in decline. A 60-day comment period on including these amphibians under ESA began on December 13. To submit comments visit regulations.gov and search for docket number FWS–R3–ES–2024–0152. Monarch butterflies in North America are grouped into two long-distance and migratory populations. The eastern population is the largest. It overwinters in the mountains of central Mexico. The western migratory population overwinters in coastal California. In the 1980s, over 4.5 million western monarchs wintered in coastal California, and an estimated 380 million eastern monarchs wintered in Mexico in the mid-1990s. Today, the eastern population has declined by about 80%, the western population by more than 95%. The western monarchs are at greater than 99% chance of extinction by 2080, the easterns between 56 to 74% of extinction. Threats to monarchs include loss and degradation of breeding, migratory and overwintering habitat; exposure to insecticides; and the effects of climate change. Public comments for the monarch listing will be accepted through March 12. To submit comments visit regulations.gov and searching for docket number FWS-R3-ES-2024-0137. To help conserve monarch butterflies, visit: https://www.fws.gov/monarch. The ESA prohibits the “take” of species listed as endangered, which includes harming, harassing (such as removing from the wild), or killing the species. The listing also mandates that federal agencies consult with the Service to ensure the species’ conservation.

Minnesota to Discontinues Deer Culling in Three CWD Areas

Chronic wasting disease in three southeast Minnesota deer permit areas has reached endemic stage and Minnesota intends to adjust its CWD management strategy accordingly. Photo: Ben Buechel/Unsplash

The Minnesota Department of Natural Resources (MDNR) will discontinue targeted culling in deer permit areas (DPAs) 646, 647 and 648, in the southeast corner of the state, where chronic wasting disease has reached endemic stage – a point where current methods of management are no longer effective. When CWD prevalence reaches 5% or greater, the disease has reached a threshold where research shows culling is not effective at controlling its spread. Therefore, MDNR’s management strategy is going to shift to other CWD management tools within this zone while working to prevent the spread of the disease beyond these areas. This, MDNR says, follows its CWD management plan developed in 2019 and updated in July 2024. “While it is disappointing that CWD prevalence has been increasing in these areas, it still remains relatively low compared to neighboring states, and we have not given up efforts to minimize its impact,” said Wildlife Health Program Supervisor Michelle Carstensen. “There are still many opportunities in these DPAs and statewide for hunters and landowners to engage in the fight against CWD, including participating in liberalized hunting opportunities, getting deer tested for the disease, and following safe carcass disposal guidelines.” Even though DNR is not pursuing targeted culling, landowners and hunters can still help manage CWD in these areas by actively participating in opportunities to increase antlerless deer harvest, abiding by carcass movement restrictions (mndnr.gov/deerimports), obeying feeding and attractant bans (mndnr.gov/deerfeedban), and participating in additional hunting opportunities. Outside of the DPAs where CWD is now endemic, MDNR will continue to focus on early detection of new cases through sampling efforts and employing aggressive actions to contain the spread, including culling where targeted operations are needed and effective. Visit mndnr.gov/cwd for more information.

Fishing Line Disposal

An eagle with fishing line wrapped around its leg Photo: AZGFD

Arizona’s Game and Fish Department (AZGFD) wants to remind anglers of the importance of properly disposing of monofilament fishing line. AZGFD biologists recently removed a line-tangled fledgling from the wild and took it to wildlife rehabilitators. Nest watchers at Willow Springs Lake noticed the eaglet with fishing line wrapped around one of its legs. AZGFD biologists tried to reach the eaglet several times but had to wait until the eagle fledged before they could capture it and remove the line, which caused a severe leg wound. Fishing line can immobilize wildlife by wrapping around its legs or securing it to a stationary object, but starvation is the most common demise. Fishing line can last up to 600 years in the environment, so it’s important to dispose of it properly. Any trash can will do. Also, thanks to the Monofilament Recovery Program, there are 85 recycling bins for monofilament at Arizona lakes and rivers. Many target bald eagle breeding areas and high-use recreation sites.

Montana Off-Road Case Results in Citations

Riding off road comes with rules in most states, follow them. Photo: Aleksandrs Karevs/Unsplash

Montana Fish, Wildlife and Parks (FWP) game wardens recently issued citations to four individuals in a recent Big Hole River off-roading case and are urging drivers to stay on designated open roads to minimize impacts. FWP first became aware of the incident when videos posted online showed side-by-sides driving in the Big Hole River at Salmon Fly Fishing Access Site near Melrose. The incident received lots of publicity, which led to several tips from the public that helped wardens gather information. Four individuals were cited for violating Montana’s rules prohibiting operating a vehicle off authorized routes. The citation came with a $135 fine. Signs posted at Salmon Fly Fishing Access Site advise visitors off-road travel is prohibited at the site. However, many roads and trails throughout Montana may not be signed but still subject to restrictions. Motorists should be aware that roads and trails may be closed to all or certain types of motorized travel at different times of the year. Staying on designated roads and trails helps protect resources from erosion, noxious weeds, soil compaction, habitat damage and negative impacts to aquatic and terrestrial wildlife.

Missouri’s Brown-Headed Nuthatch Reintroduction

The Missouri Department of Conservation and its partners finished a third round of brown-headed nuthatch reintroduction by releasing 95 birds in Mark Twain National Forest recently. Photo: MDC photo

The Missouri Department of Conservation (MDC) and partners recently finished phase three of brown-headed nuthatch reintroduction efforts in Missouri’s Ozarks by releasing 95 birds in Mark Twain National Forest. MDC released 102 birds in 2020 and 2021 into the forest as part of a pilot effort to achieve a holistic ecosystem restoration of Missouri’s shortleaf pine woodlands. Brown-headed nuthatches are only found in pine-woodlands where the pines are mature, the canopy is mostly open to sunlight, and there are plenty of well-decayed snags for nesting. The birds were likely extirpated from Missouri in the early 1900s when the last large swaths of shortleaf pines were timbered. The Ozarks regrew a mostly oak-hickory forest, unsuitable for Brown-headed Nuthatches. However, decades of pine woodland restoration by the Mark Twain National Forest returned brown-headed nuthatch habitat to the landscape. A portion of the birds were fitted with a tiny radio transmitter and are being monitored using a local array of automated telemetry Motus towers. Partnerships were key in making this conservation possible, involving nearly a dozen state, federal, and non-government organizations which came together to capture, translocate, and release brown-headed nuthatches. For more about the brown-headed nuthatch, visit https://mdc.mo.gov/discover-nature/field-guide/brown-headed-nuthatch.

$750,000 North Dakota Grant to Help Big Game

The Mule Deer Foundation approved a grant that will help North Dakota make fences safer for big game passage, increase landscape permeability and to reduce habitat fragmentation. Photo: christie greene/Unsplash

The Mule Deer Foundation (MDF) recently approved a $750,000 grant from the North Dakota Industrial Commission’s Outdoor Heritage Fund. The grant will be used to support MDF’s efforts to enhance big game connectivity and reduce habitat fragmentation in western North Dakota. One of the most significant challenges deer, elk or moose face is the presence of fences. While fences are essential for managing livestock, marking property boundaries and protecting natural resources, they can also impede wildlife movement, causing stress, injury, even death. The primary goals of this project are to make fences safer for big game passage. Over the next five years, MDF aims to modify or construct over 60 miles of wildlife-friendly fencing, facilitating safe movement and improving habitat connectivity for big game species in western North Dakota. Visit muledeer.org

Ohio Timber Theft Case Resolved

Timber thieves stole more than 300 trees from state-owned ground in Ohio

The Pickaway County Common Pleas Court recently sent a message that timber thieves will be held accountable. The court ruled in favor of the Ohio Department of Natural Resources (ODNR) in a recent case where it was determined three people illegally took more than 300 trees from state-owned land. None of the defendants appealed the judge’s ruling. The court found John C. Knauff, Joseph Knauff, and Jonathan Knauff liable for trespassing, conversion and unjust enrichment as a result of their unlawful taking of trees. The three defendants admitted in court that they entered the state-owned canal lands, cut down 315 trees and sold the timber for a profit. ODNR was awarded a total of $85,805.98 in damages. A portion, $35,805.98, was for the value of the trees and $50,000 for property restoration costs.

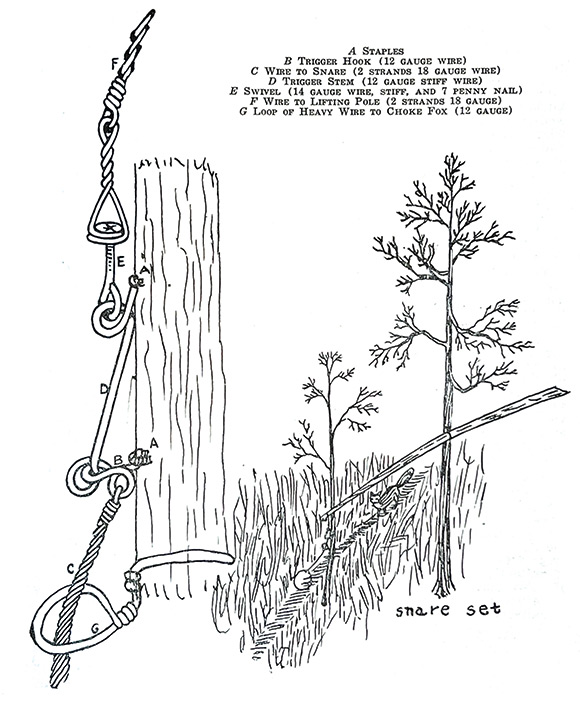

More About Fox Snaring

100th Anniversary Historical Article from January 1926

Snare set illustration. (Click image to enlarge)

By John W. Zettle

I thought I would give some of my experiences for the benefit of the trapper who would like to try or who has tried to snare foxes and had the same trouble I had at first.

The main trouble in snaring foxes is not to catch them, but to hold them after they are caught. It’s not easy for the beginner to catch them unless he has had some experience with foxes before, or unless he is a born trapper or a quick learner.

The main thing in snaring foxes is to make your sets so that the surroundings have not been disturbed and everything is looking natural, the same as before the set was made.

I use the lifting or balance pole exclusively, as I have found it to be the best method of killing them. The spring pole may be all right in certain places and under certain conditions, but it is useless here in Pennsylvania in winter, as it freezes on cold nights and will not spring up, thereby giving Mr. Fox a fine chance to twist the wire off and escape.

I make my lifting poles of dead chestnut, pine or anything handy that will answer the purpose. It should lift a weight of 15 or 20 pounds high enough to get all four feet well off the ground or snow. If a fox can touch ground with his feet, he can do some tall toe dancing and will twist the wire off much sooner.

The pole should be placed back from the trail on a convenient tree so that the small end will reach the trail or the tree to which your trigger is attached.

All fresh marks on the pole made by trimming and cutting down should be rubbed with charcoal or smoked black pitchknots or birchbark, as a fox has a keen eye for such things and is easily put on guard.

The lifting pole is fastened to the tree on which it is to swing by wire and should be taken down in the spring if it is fastened to a valuable young tree since it may ruin or hinder its growth. We must take care of the forests if we wish to have game to hunt and trap in future years.

I use six B guitar strings for the loop braided together. They make a strong collar for Mr. Fox, and one that is difficult for Mr. Fox to escape from. The wire being silver-plated does not rust so soon as common iron wire, it is strong and springy, hard to twist up, and is not easily bitten off. You may think they are expensive, but if properly set, a line of these snares doubles your money many times. The strings can be bought at any mail order house for about 40 cents a dozen, and that will make two snares. They only last one season at most and should not be depended upon after two foxes have been taken in one snare.

I make my loops with a small loop on each end, one to fasten to the wire running to the trigger and one for the large loop to slide on.

After a fox is caught, he will have the wire bent up pretty well where it closed about his neck, and where he chewed at it. I just reverse the loop, taking it off the wire running to the trigger and putting the bent-up end on, using the smooth end for the large loop. These small loops should be made large enough to work smoothly on the loop. If it works too hard, the fox will notice it and back out.

I do not clip the knots off the strings till after I have braided them, as the knots can be slipped into a slot or over a nail. This makes the strings easy to hold when braiding them.

From the loop to the trigger, I use two strands of No. 18 gauge wire twisted. This wire can be bought cheap and is just right for the purpose. It will stay any way you bend it, which means a lot in placing your loop over the trail. If you don't think so, wait and see.

I also use it from the trigger to the lifting pole and in fastening the lifting pole to the tree it is to swing on. I use eight or ten thicknesses here, twisted hard. I wrap it around the tree first at the desired height, which is sometimes hard to figure out, and give it several twists, then put up the pole and twist it tight around the pole. Thus, the pole can work freely and will do all that is expected of it.

The trigger is made from a very stiff heavy wire, about No. 12 or thereabouts, and the swivel I make of a lighter wire and a nail. The trigger and swivel are fastened together. The swivel is very important since it prevents the fox from twisting the wire or from twisting it hard enough to escape. The trigger is fastened on a tree near the trail where the snare is to be set by means of two fence staples driven into the tree. One is driven clear in just so the wire of the trigger will hook under it and not slide up under, and the other is driven only far enough to hold good – about halfway – so the hook on the trigger can release easily. Small fence staples are plenty strong enough for this.

The trigger is made in three parts: the main stem, the hook and the swivel. The trigger should not have a stem longer than 3 or 4 inches, and the hook should be as short as it can be made.

The snare loop should be about 7 inches in diameter. The loop should not be more than 7 or 8 inches off the ground. Positioned this way, the snare will catch a fox that might step through the loop in front of the hips. Then it’s goodbye for Mr. Fox, since he cannot reach the wire with his teeth and cannot struggle near so hard as when caught by the neck. They are always dead when I check my snares. I once caught a red fox this way. The lifting pole not being strong or heavy enough to lift him, he merely tied, and when my brother came by, he saw him looking at him, not knowing I had a snare there. My brother shot the fox with his .22 rifle, and you can imagine his surprise when he found him in my snare. This happened years ago when I was just starting to get on to the snare, as a fellow does not learn it all at one time.

If you place your snare 12 or 14 inches from the ground around here, a fox will walk under it nine times out of 10.

The trigger I use has been perfected by myself and I have never seen any like it anywhere. It has never failed me and springs easily in the most trying weather conditions. I experimented four years with different triggers and finally hit upon this one and have stuck to it ever since.

I place another wire with a loop of about 3 inches on the tree where the trigger is attached and run the wire from the snare through this loop, so that when the snare springs, it will draw the fox up against the loop and choke him. The same kind of wire, No. 18 gauge, may be used for this loop but a heavy wire is much better, as the connection where the snare wire and the wire running to the trigger are connected will not catch on the large wire near so soon. I make these connections so they will not catch, but some fellows are not very careful of such small matters. The loop of the snare should be hung on bushes.

After I have everything fixed in place and the snare set, I take white birch bark and smoke the snare and trigger and everything I have touched. The smoke takes the brightness from the guitar strings and prevents them from shining, and it also prevents rust to certain extent on the other wire and trigger. It will take a little time to set the first ones, but in a little while you can set them in a few minutes.

Do not experiment with triggers. Use mine and you can't go wrong. Be sure your pole will lift a fox off his feet, as he cannot spoil the trail if he cannot reach it. Be sure all connections are strong enough to hold, as the lifting pole gives it an awful jerk when it springs, especially if it is heavy. If a snare is set in a trail you use, never walk around a snare, step over it, since a fox will almost always follow your tracks.

The snare has several advantages over the steel trap. It will work in all kinds of weather and kills the fox. Rabbits and pheasants and other small game cannot or do not bother it but pass through under where a steel trap would catch them. Deer also step over the snare. These snares will catch and hold wildcats the same as fox, but a heavier pole should be used for them, as an old tom is heavier by far than a fox.

The only backset in snaring in most communities is dogs. They will get in a snare, and even if it cannot lift them, it puts an end to their hunting unless rescued mighty quick.

Old trap-shy foxes are easily taken in the snare if it is set right.

UPCOMING EVENTS

Foothills Trappers, Fulton Montgomery Trappers Fur Auctions

The Foothills Trappers and the Fulton Montgomery Trappers will hold fur auctions February 1 and April 12, at the Veterans of Foreign Wars (VFW) Post, 131 Mohawk St., Herkimer, New York. Call Paul Johnson (315) 867-6565 or Neal Sowle (518) 883-5467 for more information.

Idaho Trappers’ Association 2025 Calendar

The Idaho Trappers’ Association (ITA) will hold fur sales on March 8 and 9, at the Elmore County Fairgrounds, in Glenns Ferry, Idaho. ITA’s Summer Convention will take place June 13 and 14, at the Lemhi County Fairgrounds, in Salmon, Idaho. And ITA, in conjunction with the National Trappers’ Association, will hold their annual banquet September 6, at the Shoshone-Bannock Casino, in Fort Hall, Idaho. For more information on any of these events, contact Rusty Kramer, ITA President, at (208) 870-3217.

Indiana State Trappers’ Association Fur Sales

The Indiana State Trappers’ Association (ISTA) Fur Sales will take place on February 8, in Peru, Indiana, at the Miami County Fairgrounds. You must be an ISTA member to sell. Lot numbers can be purchased prior to the sale date. Doors open at 8 a.m. Sales begin at 9 a.m. Eastern Time. Fur buyers from several states will be in attendance. The events include food, trap raffles, 50/50 contests and other activities. Come for the fun and enjoy the largest fur sales in Indiana. For more information call or text Byron Tiede at (219) 863-3803.

Upper Peninsula Trappers’ Association Kids Workshop and Convention

The U. P. Trappers’ Association will host its 20th Annual Trappers’ Workshop for Kids and beginning trappers on Saturday, February 1, in Hermansville, Michigan. Free trapping supplies will be available for all kids attending. And kids will be building items to take home and use on their own traplines. Other activities include trapping demos, a fur buyer and a supply vendor. Contact Mike Lewis at (906) 774-3592 or visit www.uptrappers.com for more information.

Also, the U.P. Trappers’ Association will hold its U.P. Trappers’ Convention and Outdoor Show July 11 and 12, in Escanaba, Michigan, at the U.P. State Fairgrounds. Camping and food will be available on the fairgrounds. Activities will include demos, mini raffles, can raffles and a new “kids cave.” Contact Roy Dahlgren (906) 399-1960 or email trapperroy@outlook.com, and visit www.uptrappers.com for more information

Illinois Trappers’ Association

The Illinois Trappers’ Association will be hosting a fur sale Saturday, February 15 at the Krile Auction House in Strasburg, Illinois. Doors open at 7 a.m., with the first lot to go under the gavel at 9 a.m. All fur will be sold in trapper graded lots. There will be help available to grade fur. All fur is to be skinned or dry. However, otters, bobcats and badgers may be sold on the carcass. Prices were excellent last year, with the buyers asking for more fur. Buyers once again from Illinois and surrounding states are expected to be in attendance. Food will be provided. Contact Ryan Ruhl at (309) 368-2523 or bhfdto@gmail.com for more information.

New Mexico Trappers’ Association Fur Sales and Rendezvous

The New Mexico Trappers’ Association (NMTA) will hold two Trappers’ Fur Sales, one on February 28, another on March 1, at the Torrance County Fairgrounds in Estancia, New Mexico. NMTA’s rendezvous is scheduled for June 13 and 14, at the Mountain View Christian Camp, in Alto, New Mexico. Contact Shelly (575) 649-1684 or gypsytrapper@yahoo.com.

West Virginia Trappers’ Association Fur Auction

The West Virginia Trappers’ Association will hold their annual spring fur auction February 28 through March 2, at the Gilmer County Recreation Center, 1365 Sycamore Run Road, in Glenville, West Virginia. Vendors will be present throughout the weekend. Consignment for finished fur starts at 9 a.m., Friday, February 28, and again on Saturday, March 1, at 9 a.m. Dealers’ lots are graded at the end of each day. The Fur Auction will be held Sunday, March 2, at 1 p.m. Contact Jeremiah Whitlatch at (304) 916-3329 or visit www.wvtrappers.com for more information.

The Independent Furharvesters of Central New York

The Independent Furharvesters of Central New York will hold a fur auction Saturday, March 1, at the Pompey Rod and Gun Club, 2035 Swift Road, Fabius, New York. Check in furs at 8 a.m., auction starts at 9 a.m. Contact Ed Wright, (315) 427-7136 for more information.

Vermont Trappers’ Association

The Vermont Trappers’ Association will hold a fur auction on Saturday, March 8, at the White River Valley Middle School in Bethel, Vermont. Doors open at 6 a.m., the auction will take place at 9 a.m. Contact Dan Olmstead (802) 464-6344 for more information.

Central Maine Trappers

The Central Maine Chapter of the Maine Trappers’ Association will hold its annual Spring Fur Auction April 27, at the Palmyra Community Center, 768 Main St., Palmyra, Maine. Doors open at 7 a.m. For more information, contact Ted Perkins at (207) 570-6243.

Texas Trappers and Fur Harvesters Association

The Texas Trappers’ and Fur Harvesters’ Association Spring Rendezvous will be held April 25 - 26 at the Mashburn Event Center, 1100 7th Street NW, in Childress, Texas. For more information visit www.ttfha.com

New England Trappers

The New England Trappers (NET) will hold their NET Weekend August 14-16 in Bethel, Maine. Contact Neil Olson (207) 875-5765 or (207) 749-1179 for more information.

Coming in March

Features

A Smokepole Gobbler - Darren Haverstick enjoys a spring gobbler with Sweet Rachel, his muzzleloader shotgun, on the family farm in Missouri.

Rocky Mountain Theatre - Judd Brooks takes readers on a Montana mountain lion hunting adventure over his hounds.

Wild Brookies in Beaver Country - Frederick Prince shares how to find and fish beaver ponds for brook trout.

Close to Home: Trapping the City Limits - Phil Goes and sons Huck and Hugo discover that there’s a good bit of fur to be found close to home, even in the city limits.

The 1,000 Mile Detour - Faced with bad winter weather, Garhart Stephenson decides to detour for Nevada chukars, Arizona quail and Nebraska pheasants.

A Game Plan for Fishing Yellowstone - Vic Attardo helps you plan a summer fishing vacation to Yellowstone National Park’s many famous trout waters.

Other Stories

A DIY Out of State Trapline - Brent Bonecutter shares how he moved his trapline from Utah to Arizona for an extended season.

Wolves of the Birchwood, Chapter 7 – The continuing adventures of Lew and Charlie

Turkeys on a Budget – Ron Peach shares his tips for reducing the costs of spring gobbler hunting.

Pointing Out the Trial - Miki Collins remembers how she, her brother Ray and sister Julie shared Slim Carson’s Alaska trapline in the mid-1970s

The Importance of Gobbler Set Up – Wade Robertson says how you approach a gobbler can mean the difference between success and eating tag soup.

Upcoming Events – What’s happening in the trapping world.

Timber Wolves (100th Anniversary article) – O.A. Tobiason recounts his experiences with timber wolves in the Northwoods at the turn of the 20th century.

A Reptile Problem - Lucas Byker and his son went fishing on the Tamiami Trial in Florida and had some close encounters with alligators.

The Coon Hunt – W.D. Baker recalls his first coon hunt over hounds, following his friend Art’s brother-in-law Darrel Lee on a wild chase.

End of the Line Photo of the Month

Lee Johnston, Richburg, New York

SUBSCRIBE TO FUR-FISH-GAME Magazine